Years ago I wrote how Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, with its complete disregard for Stephen King’s source material outside of the stray bits that interested the filmmaker, represented the ideal approach to cinematic adaptation. Within that piece, I said the following about Shelley Duvall and her portrayal of Wendy Torrance opposite Nicholson’s Jack:

Duvall's is a performance that is similarly maligned, though for very different reasons than Nicholson's. Far from being the weak character that many would peg her as, Wendy is every bit the long-suffering wife of an abusive husband, constantly explaining away his outbursts to herself and others (let us not forget that in order to be a strong character one does not have to literally embody strength, but be fully-fledged, multidimensional, and believable given the context of the film). Duvall's representation of a woman pushed to the absolute psychological limit is nothing short of masterful, and anyone who disagrees is likely assuming that they would react any better to some of the more outlandish events that she is forced to endure. Or, frankly, a little sexist - there is a tenor to the way that some people refer to her in relation to this movie that is similar to those who rail against the wives of TVs great male anti-heroes of recent years. There are a lot of people who enjoy The Shining on the level of wanting to watch Jack be Jack at his psychotic best (to be fair, one of the film's many delights), and I think they tend to see Wendy as standing in the way of allowing him to become the fully unhinged personality that they on some level want him to be (and also, given the well-reported difficulties between her and her director, of standing in Kubrick's way as well). Duvall is one of the great screen presences of the 70s and early 80s, and her performance here is way too often overlooked.

The context of this piece did not allow me to elaborate on a key statement above: Duvall is one of the great screen presences of the 70s and early 80s. This is, frankly, an understatement. While The Shining may certainly be her most popular and widely-seen role (aside from maybe Altman’s Popeye or, to younger viewers, the run of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre), her place in the firmament is secure even without it. By the time Kubrick’s film finally hit theaters, she had spent nearly a decade as a member of Robert Altman’s repertory, and was thus a key component of some of the greatest and most important films of one of the greatest and most important periods in American film. Discovered in her home state of Texas by the director while he was working on Brewster McCloud, Duvall was inserted into the film as the love interest for Bud Cort’s lead character based solely on her presence - a distinctly Altmanian decision that nonetheless speaks to the commanding force of Duvall’s persona. The same year as Brewster she gives an almost-entirely wordless performance in his McCabe and Mrs. Miller, holding the screen with her eyes alone, after which she gets a co—leading role with Keith Carradine in Thieves Like Us. She will go on to appear in Nashville, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson; she makes her first non-Altman appearance in Annie Hall as a loquacious Rolling Stone reporter in 1977. It’s around this point that production of The Shining begins in 1978 and takes over her life until the dawn of the 80s. She comes back to Altman for his adaptation of Popeye, filmed after The Shining and released the same year, after which the careers of both run into something of a buzzsaw in an 80s film landscape that becomes immediately hostile and uninviting to the kinds of unique and idiosyncratic artist that both were.

And yet she continues to work in film and TV through that decade and well into the 90s. She retires from acting around 2002, and it is around this time that she begins to succumb to rather serious mental health issues, as she largely disappears until Dr. Phil ghoulishly shines a spotlight on her in a rather exploitative episode of his talk show in 2016. While dubious at best in intent and fairly unpleasant to watch, this episode does seem to revive public interest in her career and well-being.

I don’t want to focus on the mental-health stuff here - I don’t know a ton about it, and there has been extensive writing on her post-fame life from others who have done the proper diligence, including actually talking to her. Many were eager to pin her decline squarely on Kubrick, given what we know about the rather tempestuous relationship they had and the sometimes-manipulative tactics utilized by someone who, while perhaps the greatest film artist of all time, had no idea how to actually get a performance out of actors. And yet even this seems colored by the limited glimpses of it received via Vivianne Kubrick’s documentary on the making of the film; Duvall continued to work for years after the fact, and Lee Unkrich - who has written the definitive making-of account and even was able to meet and speak with Duvall as part of his research - insists that the stories of her destruction on the set have taken on a somewhat exaggerated life of their own. The truth, as ever, is probably somewhere in the middle.

Duvall was not a trained actor, and yet she is one of those people who seems to have been born to be in movies. While she seems to emerge on screen fully-forms, through her work with Altman she develops - or perhaps unearths - a level of craft and talent equal to any other actress of the era. She is one of the trio of actresses whose reactions make the “I’m Easy” scene in Nashville one of the most affecting and brilliantly-calibrated of all time. And she is crucial to a key scene in The Shining that establishes so much of what is important for that film to work:

In the film, Danny is visited by a Doctor after his latest interaction with imaginary friend (and personification of his precognitive gifts) Tony gives him a peek ahead at some of the horrors in store over the course of the family's winter residence in Colorado. It is after this visit, and Danny's confession to the visiting pediatrician of Tony's existence, that we first hear of Jack's outburst. The way that Shelly Duvall, as Wendy, relates this story, still attempting to convince herself as much as everyone else that it was a one-time slip - and that, hey, when you think about it, it ultimately wasn't all that bad after all because it made Jack stop drinking, right? - all while the damning ash continues to accrue on the tip of her cigarette like Pinocchio’s nose and the doctor stares at her in silent disbelief, tells us everything that we need to know about the Torrances [2]. This is a family in deep denial about their problems.

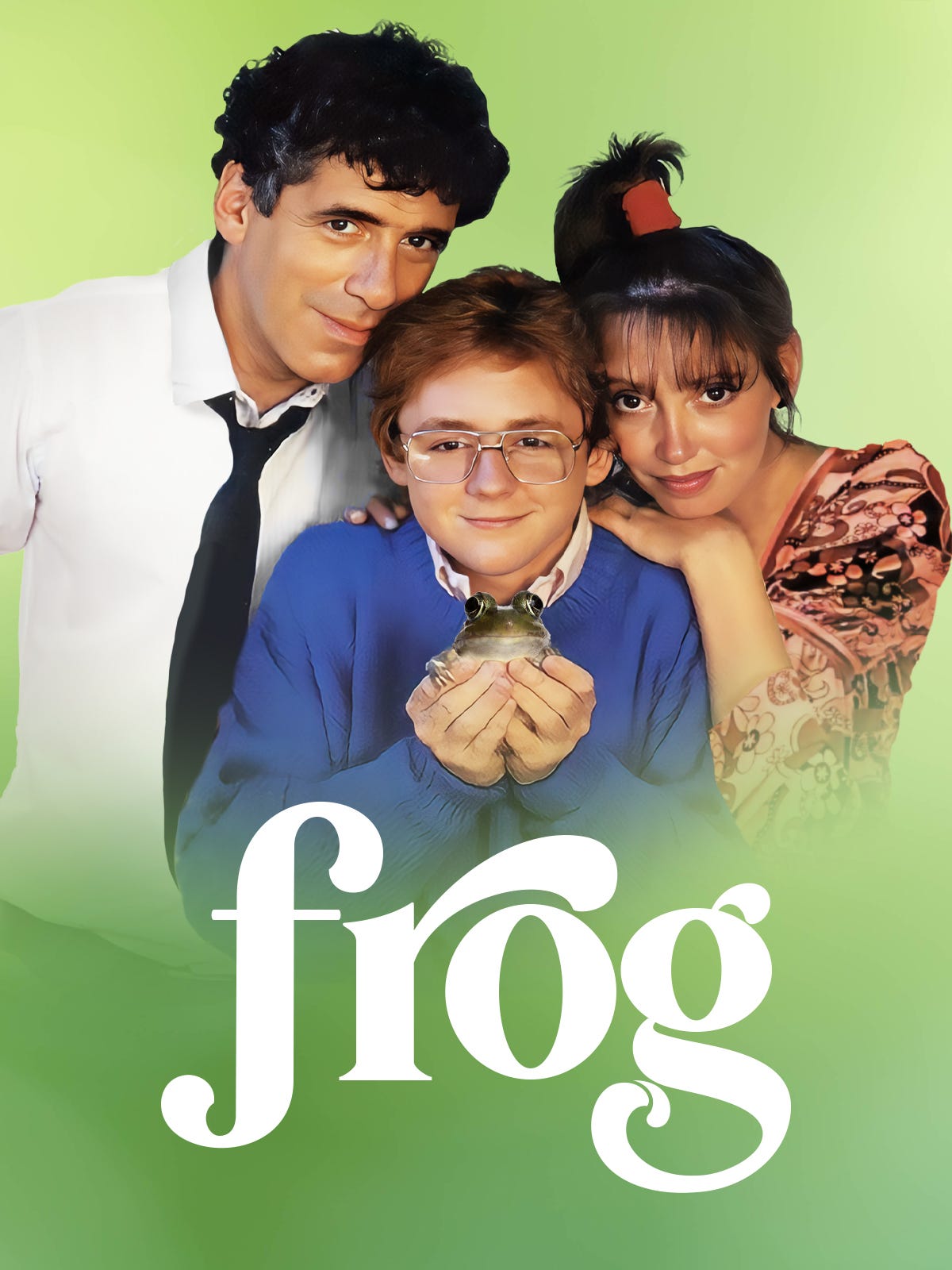

I most certainly would have first seen Duvall as Olive Oyl in Popeye, long before I even knew who she was. I would also be remiss if I were to not mention her role in Frog1 as the mother of Arlo, a young dweeb who comes into possession of an amphibian in which Paul Williams has been trapped. I have vague memories of Faerie Tale Theatre, but it does not possess the hold on me that it does to younger generations. In fact I might remember Tall Tales and Legends more keenly?

In any event, I want to highlight what may be her greatest performance - one of the greatest of the decade, perhaps - in Altman’s 3 Women. A still under-seen and underrated (though that’s been changing in recent years) film, it represents in many ways the end of the free-wheeling, experimental approach to filmmaking that Hollywood allowed through the 70s as well as the end of Altman’s first peak period as a director. And while it represents the high point of a dream-like, purely painterly mode that he would employ at times throughout that decade, the film rests entirely on the shoulders of Sissy Spacek and, perhaps especially Duvall as two of the titular 3 women. The basics of the plot - as much as that matters in an Altman film and in particular this one - are that Spacek plays Pinky, a young woman who becomes a co-worker and roommate to Duvall’s Millie and quickly comes under her thrall. Millie is vain, self-absorbed, and spends almost the entirety of the first chunk of the film in a near-constant monologue whenever she is on screen. It is a captivating tour-de-force that, even before the movie makes its big shift and the two women seem to blend together and swap identities, presents an exterior facade that hides a vulnerable and insecure interiority. It’s a performance of incredible skill and pathos that, as the movie reveals its deeper secrets and coils into further mystery, reveals itself as an absolute tour de force.

Well-reviewed at the time, the movie slipped into obscurity immediately upon release, unleashed as it was on a public that had already moved on from the New Hollywood revolution of the late-60s and early-70s to the dawning blockbuster era represented by Jaws and Star Wars. And yet it is perhaps the point where Duvall stakes her definitive claim as one of the great screen actors of her generation. And while it is based on this performance that she gets the role in The Shining, with Popeye following shortly after, it is also the beginning of her last stand as a star of major movies. It is one of the great failures of the modern age that we no longer seek out her type, nor even make the kinds of films that can accommodate another Shelley Duvall if we even had one.

-cs

Also my introduction to fellow Altman staple Elliot Gould, who played her husband.