Rhinoceros

A theatrical adaptation inspires me to touch base with one of my favorite writers while lamenting the woeful lack of the absurd in cinema, and consider the ways in which it might help us move forward.

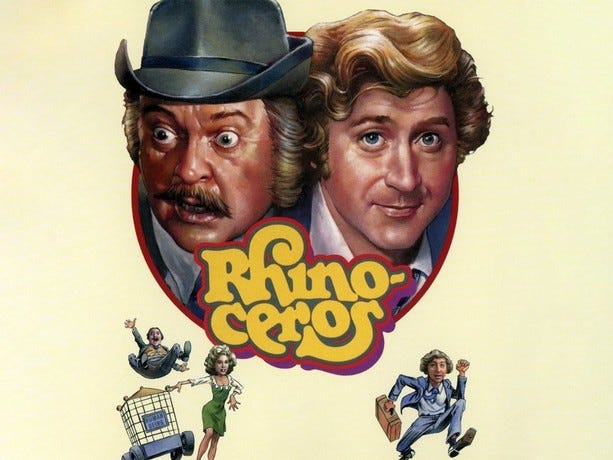

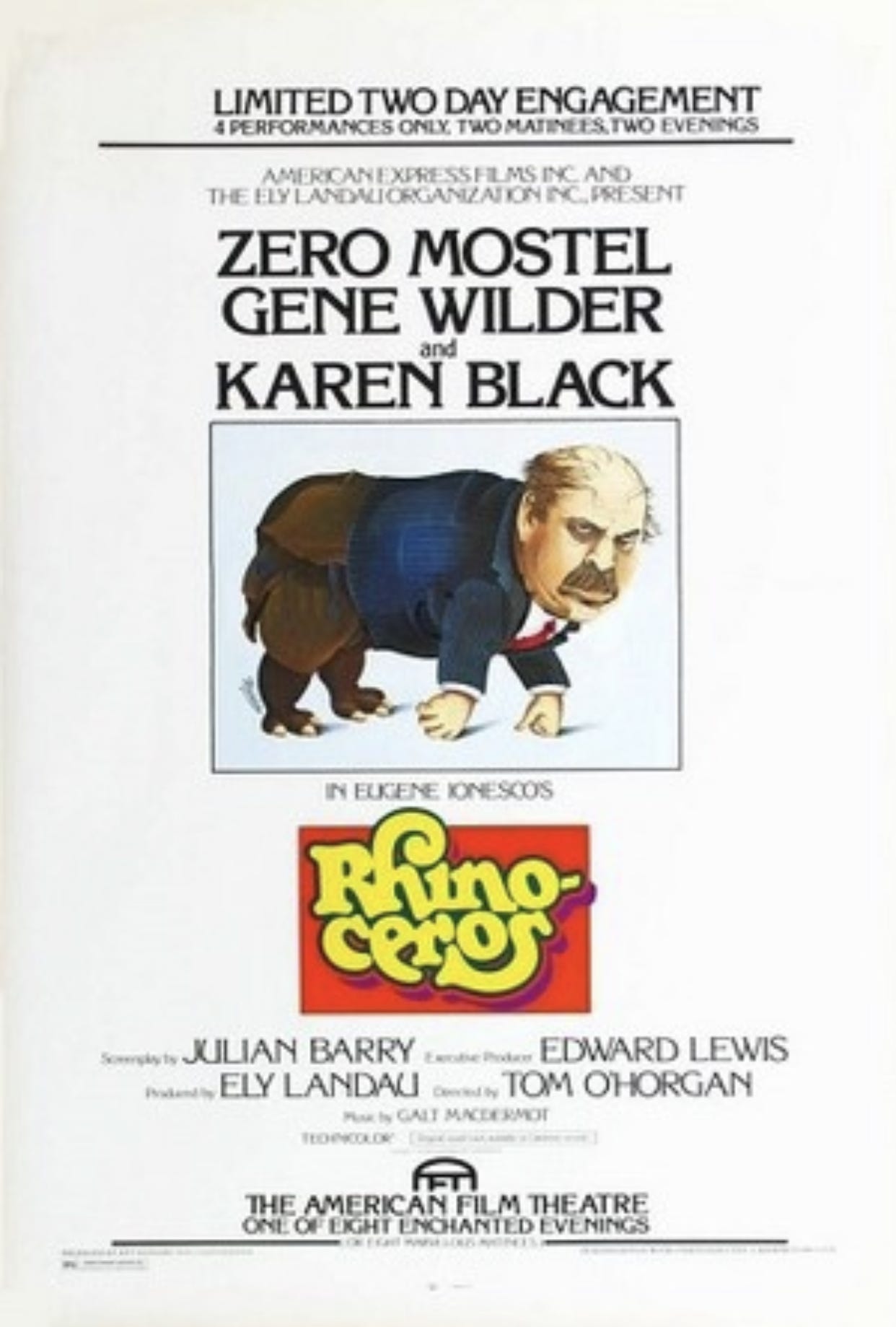

I had known for quite some time that there was a film version of Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros starring Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder and yet somehow, despite the fact that the first portion of this sentence is one of the most blissfully crazy things to imagine, I never watched it until this past week. I even bought the blu ray over a year ago, having grabbed it during one of Kino’s regular sales only to leave it sitting unopened in my office. I try not to question inspiration, and so I have no idea why it struck me to watch it once I got the ultra-rare night to myself this Wednesday but it did and so I did.

Ionesco is a pretty major figure for me, even though I came to his full catalog fairly late. When we lived in Austin for a year I worked at a used book store and one of the sections I was assigned to stock and keep rotated was Drama, which meant that I spent most of the time I should have spent working poring through the backroom stock and picking and choosing which books I wanted for myself. It was a perfect opportunity to catch up on works that I hadn’t yet had a chance to read. One of these was Martin Esslin’s The Theater of the Absurd, which quickly took on a near-Biblical importance for me as I found something that had not only put into words a cogent explanation for so much of the instinctual pull I felt towards the more avant-garde fringes of art and literature, but had also provided me with an exhaustive database full of writers and texts that I suddenly had the joy of seeking out and discovering.

I had of course heard of the major figures discussed in the book - writers like Beckett, Pinter, Albee, and of course Ionesco. It was while reading Esslin’s book that I started setting aside any Ionesco works that came through my store while also seeking them out in other branches - including Rhinoceros, which is probably his best-known and which was the only one that I had read previously. The story of a provincial French town whose citizens suddenly begin turning into the titular pachyderm, the play has long been understood as a metaphor for the rise of fascism - specifically the move of the bourgeois intelligentsia of Ionesco’s birth country of Romania to the militantly anti-semitic Iron Guard.

While thus rooted in some very specific socio-political currents, the play is nonetheless fairly universal in its depiction of the ease with which people succumb to ideology out of, among other things, the need to conform. It is thus the kind of work that is primed for bad-faith interpretations, especially in today’s climate, and I’m relieved yet curious as to why it hasn’t turned up in an undercooked, reactionary think-piece on the evils of the woke mindset.

Perhaps it’s because despite the obviousness of the central metaphor, there’s enough nuance and complication in Ionesco’s lampooning of social pressures and human susceptibility that it remains impenetrable for those wishing to play to the cheap seats. As Esslin argues, the play can be read as being just as much about the futility of resistance as it is about the inevitability of capitulation or, at the very least, posits the troubling idea that to remain human in a society turned Rhinoceritic is a state of tragic loneliness rather than victorious resilience. Berenger’s insistence at play’s end that he will never transform comes only after he is unable to will himself to do so, and is greeted immediately by the falling curtain. One of the smarter decisions the film makes is to stage this last act of defiance with Gene Wilder climbing to the top of a rickety structure on the top of a tenement rooftop, framed less as an imposing bastion of strength and more as a precariously tottering figure with nowhere else to go. There’s no sense of moral victory as such, nor is there even the the cathartic defeat of something like 1984.

Perhaps it’s because it’s not about fanaticism propelling people to transform so much as it is about then sliding down a path of least resistance towards that capitulation. No one in the play actively chooses to become a rhinoceros - again, Berenger tries and fails to do so in the closing moments; even when they display the first signs of acquiescence to the idea of transformation, it merely happens - something that makes the story all the more frightening in its implications. There are clear analogues in both the play and the circumstances that inspired its creation in Trumpism - perhaps even more so in this second election, with its increased sense of a near-parodical normalization of abject mendacity, coupled with the truly gobsmacking sense of déjà vu (imagine a sequel to Rhinoceros in which humanity, having barely survived their bouts with Rhinoceritis, end up willfully succumbing to it yet again) which made watching the film and rereading the play a somewhat unsettling experience. This is of course though a blatantly US-centric view. One can certainly say that the text presages the rise of Trump, and of course it does in its way, but only because the trends that Ionesco is depicting here are ones that have been around before and are eternally cyclical, rooted as they are in our very nature more so than any specific political moment at which they may materialize.

Ultimately, it may be that the play has dodged the bullet of mis-appropriation because it is too obscure, or would be thought of as too much of a high-brow, intellectual piece by those who would wield it for such purposes, and doesn’t have the same level of cultural permeation as something like the previously-mentioned and oft-bastardized 1984.

That high-brow status, conferred upon anything that has even a whiff of the avant-garde even when it is as enjoyable and accessible-in-its-own-way as Rhinoceros, would seem to make the idea of a film adaptation featuring two fairly mainstream comedic stars something of an ill fit, and while the film is indeed a strange beast the casting itself is perfect because Ionesco, like Beckett before him, draws heavily on comic tropes and character types for his depictions of the human condition in all its woeful pathos. The chemistry between Wilder and Mostel is perfect for the two primary characters of the play, and Mostel even played the role of Jean on Broadway prior to appearing in the film adaptation. Where everything falls short is in the film craft and some of the adaptation choices. The film is faithful to the play in so far as it retains large chunks of dialogue, though it excises a lot of Ionesco’s wordplay, and the way that language is used to emphasize the play’s themes is thus somewhat dimmed in effect1. You would think that this was a decision made in the interests of a more cinematic approach, but that’s not really the case at all here - in fact, there hasn’t been much in the way of cinematic adaptation or re-interpretation. Director Tom O’Horgan (a noted theatre director of such hits as Hair! and Jesus Christ Superstar whose film resume is however limited to this and the Bee Gee’s Sgt. Pepper movie) rather opts to basically film a streamlined, somewhat more superficial version of the play using standard coverage (Wide shot > medium close-up > close-up, rinse + wash + repeat). O’Horgan’s blocking is fine and often inspired here, but as sometimes happens when someone moves from stage to screen direction he seems to have no idea what to do with the camera, to the extent that this ends up feeling at times like a 70s-era TV movie rather than a theatrical release.

Part of this is because the scope of Ionesco’s ideas, even when truncated, can’t help but burst against the seams of such a constrained endeavor just like one of the bi-corned heads bursting through a bathroom door post-metamorphosis. The physical, emotional, and psychological proximity of the camera gives away the cheap artificiality of the sets and decor, and as such calls an attention to them in a similar manner to the way the directorial approach leans into the comic absurdity rather than present the happenings at face value - a trap door that most cinematic attempts at the absurd or the surreal fall face-first into. It is one of the great ironies of the dramatic arts that a theatrical production, which takes place in real time and simultaneous with our physical reality, nonetheless is allowed by the other limitations of its nature a wider berth to utilize artificiality to its benefit whereas cinema, which is inherently a deception aided by technological mediation, clings as a result of decades of conditioning to as close an approximation of reality as possible (another reason why there are so precious few films that have truly nailed the delicate tonal and aesthetic balance necessary to pull off something even approaching the style and aesthetic function of the absurdists).

What we get instead is a genuine oddity - a high-minded literary adaptation with a worthy cast given a fairly pedestrian directorial treatment and approached like a cheap exploitation-level production. The score beggars belief and there is a song, used multiple times, that is such a spectacular misfit that you have to wonder whether it is a gag or a clueless studio note. (It is attached at one point to a sequence depicting one of Berenger’s nightmare, the only original scene conceived for the film, that is so obvious and heavy-handed in its dream-logic surrealism that it removes any doubt that O’Horgan may not be the person best suited to bring this material to screen).

And yet despite this I still found the whole thing compelling, and re-reading the play after watching it I realized it was even more faithful (superficially at least) than I had originally realized. But I couldn’t help but to continue to lament the fact that a true cinematic absurdism had yet to fully materialize, even when it had a perfect opportunity to hear. Though of course a further irony is that you can’t achieve this using the language of the stage - one has to be adept enough with cinematic language to really know how to undermine it, or be so versed in its use as to become completely disillusioned by its stagnation. Some have come close - the French New Wave may be the closest cinema has had to the absurdists, as they served the same purpose both aesthetically and politically, but even their disruptions have by now become commonplace and cliche. Lynch’s Twin Peaks The Return is the great absurdist text of our era, and on top of all other reasons I revere it this fact establishes it more and more upon reflection as one of the most significant works of my lifetime. But it’s also a unicorn, truly one-of-kind, and even it’s biggest acolytes within the industry seem content to apply its lessons to more mainstream fare. The time seems ripe, with both the calcification of film and especially TV form and narrative, as well as the larger sociopolitical climate we currently live in, to look back to and learn from Ionesco and his contemporaries and start to think about ways to break the form so that we can ensure that it will not only continue but maintain its relevance.

A true cinematic interpretation of Rhinoceros would have either found a method to stay true to the rhythm of the language as written rather than chop those rhythms up in the interest of editorial pacing, or would have used the stilted form on display here as a way of expressing the play’s notions that the ways in which we communicate can get flattened through repetition and cliche to the point that we are robbed of expression and, by extension, of our individual identities themselves, thus allowing an entry point for the forces that seek to transform or eliminate our humanity. In addition to the Rhinoceritis contagion, Ionesco utilizes language - inane conversations, repeated banalities - to suggest the ways in which his characters have lost their individuality well before they begin to transform (or perhaps to suggest that they were never fully distinct individuals to begin with). By treating this kind of dialogue as “movie dialogue,” and providing the kind of psychological and emotional emphasis that results from coverage, the film places an artificial emphasis on each line that defeats this purpose. Every edit makes the succeeding line something of great import by virtue of its existence.