Revisiting the Aliens Franchise

Re-Watching the four original films for the first time in many years.

This year Ridley Scott’s Alien turns 45, James Cameron is finally releasing the 4K transfer of Aliens, and the Halloweenies podcast is covering the entire franchise for their current season, so it felt like a perfect time for me to rewatch the films, which I did over the course of the past couple weeks.

As a child of the 80s/90s I am inescapably a franchise person (to an extent - they have to be grandfathered in as I basically don’t care about any series that started after roughly 2005). The fact that the Aliens quadrilogy (I suppose I should say hexology here, but I rebuke Prometheus and Covenant) is such a formative one for me, given the way I came to it, may go aways towards explaining why I care so little for things like cohesion and canon when it comes to any film series. I did not watch these films in release order, and furthermore entered into them with a collection of comically inaccurate pre-conceived notions based on things both real and wholly made up. My first exposure to this universe was via a collection of action figures released by Kenner in 1992, based on a potential animated series that never materialized and timed, I would imagine, to that year’s release of David Fincher’s Alien 3 (I should format that as Alien Cubed, since the film itself does for some reason, but I don’t know to plus I find it silly). I imagine anyone around my age has a firm memory of this toy line, which featured re-designed versions of some of the key players from Cameron’s action-heavy second installment as well as a collection of various xenomorph sub-species.

Included in each box was not only a mini-comic containing an encounter between that figure’s character and a specific alien, but also a brief bio accompanied by a thumbnail photo of the toy’s live-action counterpart. Or so I thought, since I had not seen any of the films and was not allowed to due to their R-rated, graphic nature (this being a time at which my mom was very protective of these things1; also consider that I was 9 years old). Being that this was the pre-internet days, wherein information on these matters was not particularly easy to come by, I sought my answers as to what the movie was like from that age-old source of wisdom – idiots on the school playground. I have vivid memories of David Grubbs detailing the most gruesome deaths for most of the characters I had become attached to through these figures – descriptions that left me reeling and yet also spurred me to further desperation to see such horrors. I was so deeply obsessed with a movie I had not seen that I carried around an old Trivial Pursuit card that had a question about the film on it (“Which 1986 film contains the line ‘Get away from her, you bitch!’”) I eventually convinced my mother to let me view it, provided that I watched with a friend under the supervision of a parent in broad daylight. That was why I ended up watching it in Nick Collela’s basement with his father present, though I don’t remember why he was the one I ended up watching it with.

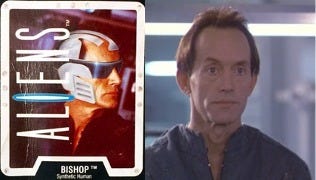

Aside from its mythic status as a coming-of-age right-of-passage (I pity the younger generations who did not have the experience of huddling in a basement, watching something you’re not meant to be watching, via a crummy standard definition transfer – you really felt like you were getting away with something and it made the viewing experience that much more indelible), this screening was strangely unsatisfying since 1) nothing I was told about the film was true and 2) the characters therein bore little to no resemblance to the toys I loved beyond their names and the occasional weapon (Drake’s Smart Gun) or piece of wardrobe (Hicks’s colonial marine regalia). I kept waiting for Lance Henriksen’s Bishop to shed his human hair and adopt his more ostentatiously cybernetic visage, but it never happened. I felt conned on multiple levels.

It was only after further reflection and multiple viewings that I was able to appreciate the film on its own terms and fully separate it from what I had been led to believe it would be.

This was the start of a long process for me of judging a film and related ancillary media as separate entities that could co-exist without one impacting my experience of the other (another big step to this end was when I read the Jurassic Park novel after falling in love with the movie and was traumatized by the differences, especially the fact that Malcolm dies in the book – well, I guess he doesn’t because he hilariously shows up in the later sequel with a half-assed non-explanation). Eventually Aliens became a favorite, and it wasn’t until several years later that I went back and watched the original Alien. My entry point here was once again a toy, as I remember having a holiday catalogue that included a wearable toy face-hugger that came with a Nostromo crew T-shirt. This has become one of my white whales – I’ve been trying to track this down for years. I don’t remember what if anything I expected from the movie. I knew about the face-hugger/chest-burster scene, not only from the aforementioned listing but also from snippets of conversations I would overhear between adults who had seen it. I don’t remember how old I was, but I was certainly still either a pre- or early-teen, and I recall finding it incredibly boring. As a male child of the action movie era, who only knew Cameron’s amplified sequel, the slow-paced tension of Scott’s movie struck me as incredibly dull, and I wasn’t old enough to pick up on any of the subtext at all.

As I have grown, and as my tastes have developed and shifted, I have come to prefer the original Alien ever so slightly to the sequel. There is something so distinctly 70s about it in the best ways – the working-class nature of the characters, the grimy lived-in quality of the mise-en-scène, the loose nature of the dialogue scenes, so clearly improvised and also shaggy in that great, relaxed way of the time, the fact that we barely ever see the xenomorph (an argument in favor of the technical limitations of practical effects) and so come to understand so little of it that remains this ineffable personification of our nightmares. Alien is genuinely frightening and upsetting, and while we understand the mechanics and the life-cycle of the creature, there’s none of the ludicrous mythologizing that would later come into play. Its motives remain unknown, but in a way that retains the almost-eldritch-horror nature of its existence. It is a creature born out of our most primordial fears, insectile and mechanical with a violent sexuality both in its design and its methods of reproduction, and we are given just enough of all of that to fill in any blanks with our own innate horrors.

Cameron’s film removes this mystery somewhat, as his xenomorphs become much more utilitarian fodder for the marines sent in to wipe them out. His characters speak largely in movie lines timed to individual camera set-ups – where the crew in Alien felt like real people, everyone here is a type even as the performances are uniformly excellent. Gone are the dark and mysterious corridors of the Nostromo and their symbolism of the unknowable depths of the human psyche – Cameron’s film is classically lit so as to better follow what’s happening, even its darker moments rich in visual detail (I should note that I’m basing this observation off of a 4K transfer that may very well have brought out highlights that were not there in the release print or previous home video editions). There’s thematic relevance here as well, of course – this is a movie about Ripley coming back to face her fear, and so the creatures are thus being brought out of hiding in way that shifts the power and agency back to her. They are also no longer slinking in the shadows of a new environment as they were in the first film – they have nested and made this colony a home, and so there’s no need for them to hide except to wait in ambush for the forces intruding upon their space.

The more brightly-exposed sets also allow for the matching necessary to integrate the special effects photography that permeates the film. And make no mistake, these are still some of the best effects committed to film. I know how they did all of this stuff and I still watch and wonder how they did it. Cameron has been able to do whatever wants with all the resources his heart could desire for so long that it’s easy to forget that he was at this point a scrappy independent filmmaker, brought up through the Roger Corman pipeline and coming hot off of the first Terminator to direct his first studio film. As such he was given a limited budget and had to rely on every effects trick in the book to achieve his vision – hanging foreground miniatures, forced perspective, front projection, mirrors to extend space, puppetry. It’s hard to believe that only 12 alien suits were made for the entire production (though you can definitely tell when they are re-using shots if you look closely), though it’s filmed in such a way that what they have is greatly maximized. Similar to the first film, the limitations become a benefit – it may still be his best-looking movie (even some of the CGI in Titanic looks a little dodgy by now). The Alien Queen herself, and her battle with the Power Loader that ends the film, is a full and conclusive argument for the virtues of practical, on-set elements rather than digital – something I’ll get to further in a bit (boy oh boy will I get to this further in a bit).

Stylistically Cameron’s film is completely different from Scott’s – Cameron shoots in 1:85 rather than scope, and he utilizes wide to standard lenses where Scott relies on longer focal lengths, which in addition to the low light and the heavy use of fog and steam gives the first film a softer, grainier look than its sharper follow-up. Cameron’s film has a militaristic fervor to the production that, as is often the case with his movies, is necessitated by the scope of what he's trying to accomplish but that also matches the narrative. Alien, by contrast, was clearly made by - and I cannot stress enough that I mean this as the highest compliment - genuine weirdos. Even Scott, with his cigar-chomping meat and potatoes straight-forwardness, has a bit of freak in him. And yet as different as they are they still feel of a piece with each other, and as Aliens ends with Ripley going back to sleep with her new make-shift family we feel like we’ve come full circle a bit.

Alien 3 is when we start to wander. There is in some ways a sense of trying to get back to the core of the original film – we’re back to one alien, everything is grimy and dingy again, and there are overtures towards dealing with things like class and gender dynamics. One of the earlier drafts of the script involved Ripley landing on a wooden satellite inhabited by monks, and this religious thread has been brought through to the final version as she instead lands on a male-only prison planet populated by murderers and rapists who have found religion. This dynamic is brought out a bit more in the longer assembly cut, but neither this nor the theatrical version really do much with it. There is a character in the assembly cut who develops a near-religious reverence for the beast, but even this ends up serving more of a plot function than a thematic one. It feels like a major missed opportunity, especially since the film is overall meaner than the previous two, and often feels like a conscious attempt to tear apart and break down what people liked and responded to in the previous installments, starting with the deaths of Hicks and Newt that open the film. One’s mileage may very as far as whether this attitude is interesting or rather it more so reflects the instincts of a young director, eager to prove himself and possessing something of an edgelord sensibility, especially at that time, as well as a star who was getting tired while also gaining producorial input. In any case, it had by far the largest budget yet of any of the films in the series, which certainly shows in the production design – and that must have been where they spent it all because the alien effects are ghastly.

Alien 3 was an instance, unlike Aliens, where everything I heard from other kids about what happened in the film before I saw it proved true – and I’m mainly talking about the ending. I didn’t see it in theaters but was very much aware of it. I have the vaguest recollection of going to see Ferngully with a school or summer camp group in a theater that was also playing Alien 3, and maybe even peeking in for a bit (I want to say a scene involving Charles Dance - maybe the autopsy scene? - because I have such vivid memories of his face imprinting on me). I eventually saw it in its entirety on home video. My brothers and I used to rent movies by the handful from the mom-and-pop video store in Eaton Rapids, Michigan when we spent summers there with our grandparents. I don’t remember much about the store except that they had a poster for Pet Sematary that scared the bejesus out of me every time we went in. I also don’t remember much about that viewing of the film – the clearest memory I have is of our father, who was living with our grandmother at the time, watching it late at night once he got home from work (dear old dad, he would always tell us to make sure to rent something that he would want to watch, though never with us). Anyway, I don’t even know if I liked it, but that was an era in which if I liked something I watched it over and over and over again (one summer not long after I watched Con Air every day for a week and then the next week did the same with Bram Stoker’s Dracula), and I didn’t rewatch Alien 3 for another several years. For some strange reason I can’t reconcile having already seen Aliens by the time I would have seen this, but I know I must have seen that first.

By the time we get to Alien Resurrection we’re basically trading in fan fiction, as made evident early on by the “Written by” jump scare we get in the opening credits (if we were not already aware). Jean-Pierre Jeunet steps behind the camera this time and so the palette is greener, the lenses wider, and the whole thing has a very 1997 feeling to it. I remember seeing Sigourney Weaver on Letterman around the time of the release and she teased that things got a little kinky in this one before blushing and explaining, with a shrug, that they had a French director. Things sure get kinky alright, but in way that’s so overt that it’s impossible to take seriously and so ends up feeling quite lame. In his Aliens commentary, Cameron says that when he first approached Weaver about appearing in his sequel that she was willing to do so as long as she got to 1) die and 2) sleep with an alien. He refused, but then notes with amusement that over the course of the next two films she got to do each. Watching Resurrection again after so long it’s unclear whether or not the assignation between Ripley and xenomorph actually happens, but it sure is pretty heavily suggested, and there’s definitely a monologue from Brad Dourif’s gleefully cocooned scientist later on about how Ripley’s DNA (shared because they were both cloned from the same source) has given the queen a human reproductive system).

The fact the last sentence of the previous paragraph can be typed about a movie that is still so tediously dull tells you everything you need to know about this one, sadly. The whole movie is wild, but not in a way that is anywhere near as interesting as it should be, especially considering the fact that the cast is stacked with a roster of dependable lunatics – not just Dourif, but also Dan Hedaya, and Michael Wincott. The aliens themselves have ceased being mysterious and have instead become nonsensical – this came out four years after Jurassic Park, and they’ve basically become raptors in this. Some of the problem here might be the incompatibility between Joss Whedon’s desire for proto-Firefly adventure tale and Jeunet’s sexually gonzo body horror. The two kind of end up cancelling each other out.

I used to be something of a defender of this one, as it was the first of the series I saw in theaters. I wasn’t yet old enough to legally see R-rated movies, but I looked old enough and theaters were still lenient enough (it wasn’t until the release of the South Park movie in 1999 that they started cracking down) that I was able to see it on my own as a freshman in high school. I remember trying to impress my then-girlfriend with tales of seeing Dan Hedaya holding a piece of his own brain, wisely deciding not to describe the scene in which Weaver murders the alien-human hybrid birthed by the queen’s newly-acquired human reproductive system by cutting a hole in a window with her acid blood and watching it get sucked inside out into space while it screams and pleads for mercy.

Like the Mission: Impossible series, the Alien films were a director’s showcase for the first four, and yet by this time it had become a franchise that was eating filmmakers alive rather than spring-boarding them to success - Fincher to this day refuses to even acknowledge 3, and only had a career because he was able to make Seven shortly after it; Jeunet never set foot in Hollywood again after his catastrophe but his next film was, somewhat hilariously, the very successful Amelie. Aliens lay dormant as a franchise for years until Ridley Scott decided to demystify everything he could about his previous masterpiece with 2012’s Prometheus and the follow-up Alien: Covenant in 2017. While I can go back and watch even the worst of the original four films from time to time, I can’t imagine ever subjecting myself to those two again.

The young man who watched these films so voraciously in his youth would go on to write a preposterous knock-off of the series based on another toy line of the time and titled Boglins, which was about a group of soldiers who return from an outer-space mission to find the planet deserted. They venture into an underground mine and realize that they have slipped through a worm-hole and are hundreds of years in the future, and humanity has been forced underground by monstrous creatures who are still hunting them down as they live in hiding.

And speaking of rip-offs, no discussion of my long-standing affinity for these movies would be complete without a brief mention of Leviathan, a particularly terrible/amazing knockoff – starring Peter Weller, Ernie Hudson, Richard Crenna, Daniel Stern, and Hector Elizondo. It’s basically Alien underwater only with worse special effects, and it’s quite possible that I’ve watched it more times in my life than the original.

-cs

At one point around this time me and my brothers were watching Robocop – not for the first time – and after Clarence Boddicker shot Robert Morton in the knee caps and decimated him with a grenade, she had what I can now understand was a moment of severe existential panic – even though (because) she was the one who showed it to us in the first place - in which she leapt out of her chair, ejected the tape, and forbade us from watching the movie again.