On The Shining, Personal Expression, and the Nature of Adaptation

I am once again solo parenting this week, and between that, summer class, and beginning the process of reviewing copyedited proofs for the textbook, I haven’t had much in the way of free time. I’ve actually written quite a bit this week, but it’s all been piecemeal and I haven’t had a chance to organize it or get any of it to cohere yet. So imagine my delight in remembering/realizing that we are within weeks from the 45th anniversary of the US release date of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, which gave me a perfect excuse to repost the below piece that has otherwise been lost to time.

Enjoy, and look out for new stuff next week.

The most elusive quality of Stanley Kubrick's The Shining may ultimately be its simplicity. A deceptive simplicity, to be sure, but one which nonetheless allows for so many mis-interpretations of what The Shining is "really" about. One only need to watch the recent Room 237 to get an idea of the extreme contortions to which people will bend in order to assign any and every hidden meaning possible to the film (each meaning being, not so coincidentally, a reflection of its respective champion's most dominant obsessions). Ultimately at the root of this willful obfuscation, of the desperation to raise its subtexts to text, is the fact that the journey of Nicholson's Jack Torrance is in no way comforting, and in fact says some very dark things about the human potential for weakness and violence. Even A Clockwork Orange, arguably Kubrick's most disturbing look at human nature, is a passionate argument in favor of free will, a noble and altruistic pursuit no matter how gruesome some of the individual steps. The Shining, on the other hand, is a grim exploration into the very darkness that lies innate within the human soul. Torrance is overtaken by this darkness, a defeat which seems further to be placed within the larger context of a cyclical nature of violence within not only Jack’s soul but the entire human character1.

That journey seems to lie at the heart of Stephen King's problems with the film. King has been very open about the fact that The Shining is one of his most personal books - that the seduction of Jack Torrance by the evils of drink and his susceptibility to the grim forces within the establishment to which he has signed on as caretaker mirror King's own struggles with substance abuse and the fear of what carnage those demons would potentially reek upon his family. As such, the Torrance of King's novel is ultimately a good, if fatally flawed, man. One who gives a little too easily to his darker impulses, and yet who is at the end afforded one last moment of redemption as he wrests control of his body from the possessing evil of the Overlook long enough to provide his son with time to escape his murderous rage.

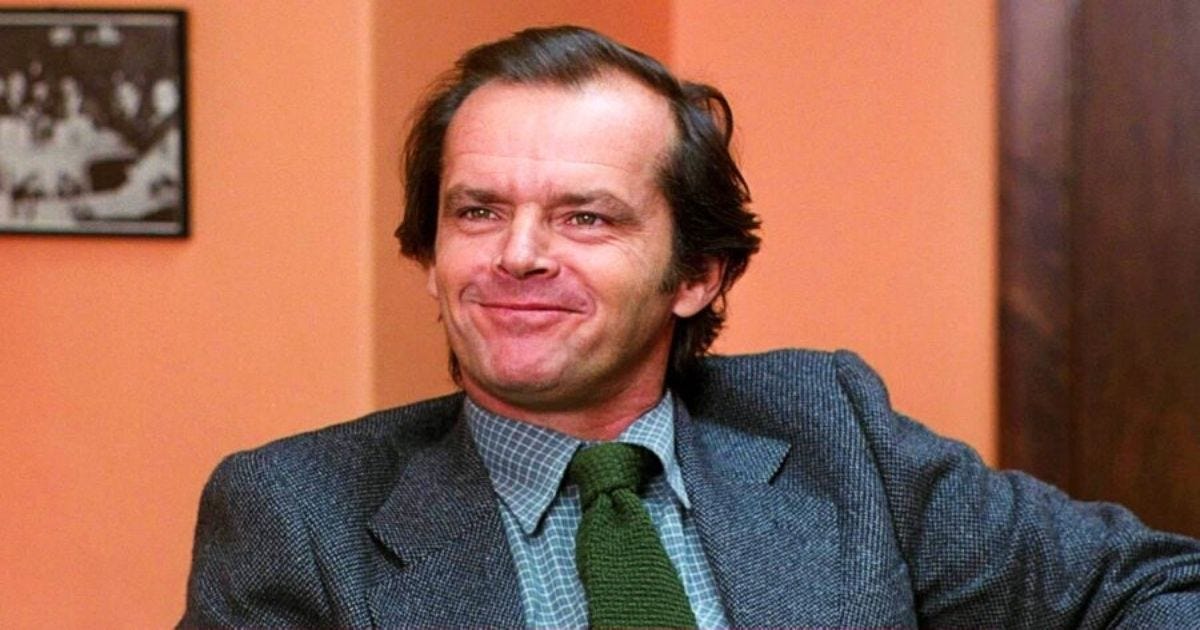

In Kubrick's film, Torrance is lost from the very beginning. A lot of the criticism of both the film and Nicholson's performance focus on this aspect, complaining that it allows no room for tragedy to have Torrance start low and sink even lower. But Kubrick isn't interested in portraying the tragic fall of a good man so much as peeling away the loosely respectable veneer of a man whose greatest tragedy is his very existence. Nicholson is not poorly performing the part of an amiable regular guy when he goes to the Overlook for his interview with Stuart Ullman - Torrance is. This is a man desperate to convince the world and himself that he is deserving of a second chance - a failed writer desperately trying to wring that ever-elusive masterpiece from the depths of his soul. (Of all the horrors that the film dramatizes with such chillingly accurate precision, none may be more potent to the struggling scribe than the mounting anger that builds within Torrance as he struggles and struggles to puke out a work that just won't come out of him, perhaps because - the greatest nightmare of all - it isn't in there to begin with2.)

Jack Torrance is a bitter, angry, self-loathing wreck. The defining moment from his past, the memory that haunts him and has been slowly injecting its poison into his relationship with his wife Wendy, is the incident in which Torrance, while just a little too drunk, got just a little too angry with his son and broke his arm while pulling him just a little too forcefully away from a pile of sullied work papers. To King, this is a terrifying mistake made at the height of a man's weakness; to Kubrick, it is a little piece of Jack's true self bubbling up from the concealed depths for a quick breath of air. And since King so clearly identifies with Jack as a character, given that he was largely trying to exorcise his own demons through him, it makes perfect sense that he would take particular offense and Kubrick’s interpretation. If Jack is irredeemable, then the implication is that he is as well. Which is not to say that’s at all what Kubrick was trying to say - the filmmaker’s clinical lack of sentimentality likely just made such considerations irrelevant at worst3.

I'm sorry to differ with you sir, but you are the caretaker. You've always been the caretaker. I should know, sir - I've always been here.

- Delbert Grady (Phillip Stone)

A small but significant difference between book and film, rarely mentioned in light of the broader changes but significant in understanding where King's work differs from Kubrick's:

In the film, Danny is visited by a Doctor after his latest interaction with imaginary friend (and personification of his precognitive gifts) Tony gives him a peek ahead at some of the horrors in store over the course of the family's winter residence in Colorado. It is after this visit, and Danny's confession to the visiting pediatrician of Tony's existence, that we first hear of Jack's outburst. The way that Shelly Duvall, as Wendy, relates this story, still attempting to convince herself as much as everyone else that it was a one-time slip - and that, hey, when you think about it, it ultimately wasn't all that bad after all because it made Jack stop drinking, right? - all while the damning ash continues to accrue on the tip of her cigarette like Pinocchio’s nose and the doctor stares at her in silent disbelief, tells us everything that we need to know about the Torrances4. This is a family in deep denial about their problems.

King's book, in contrast, features a scene in which both parents visit with the doctor after Danny's examination (which happens once the family has already moved into the hotel and has been living there for quite some time), and Jack takes it upon himself to not only confess the incident in full, but steps up and takes the blame for himself. For King's purposes, this emphasizes the idea that this is a normal, if flawed family. Yet as someone who is admittedly more connected to Kubrick's film this scene reads as quite a misstep, releasing a great deal of the claustrophobic psychology of the proceeding 200 pages, which are steeped with so much self-doubt and -loathing that they really started to get under my skin in the best of ways. In the film, the only other time it's mentioned is when Jack is ranting to Lloyd, his spectral barkeep, about how his wife still holds it against him even after all of these years and even though it was an accident. Kubrick's Torrance is a man in constant, raging denial of his own problems, and that mounting rage is one of the many pressures that slowly simmers to a boil over the course of the film. King's book, in stark contrast, gives both the reader and the Torrances a moment of catharsis - they are able to confess Jack's abuse, their marital problems, and their unspoken uneasiness about Danny's strange knack for foresight to an outside party for the first time.

Part of what Kubrick has done with his film is to refuse the audience a release of that claustrophobic atmosphere, to the great benefit of the material. There is no relapse from the mounting sense of doom that sets in right from the very first note of Wendy Carlos' synth translation of the "Dies Irae." The entire film is a building of tension right until the moment that Wendy and Danny drive away in that Snocat to their indeterminate fates (indeed, Kubrick's film is so claustrophobic that once they leave the hotel, we are given nary a clue as to what happens to them, our focus instead remaining on Jack as he freezes to death in the hedge maze and becomes absorbed into the other-worldly fabric of the Overlook).

The Torrences of the book are a couple who have stepped to the brink of divorce only to recover and step down the path of reconciliation. The Torrences of the film are perpetuating an incredibly feeble lie that has made their domestic life increasingly strained and miserable.

When all is said and done, King is ultimately a moralist, whereas Kubrick is a realist. One is the man who ended The Stand with the hand of God literally descending from heaven to detonate a nuclear bomb, while the other ended a comedy with the complete obliteration of the world at man's nuclear hand. King killed Tad Beaumont at the end of Cujo for his mother's sins, while Kubrick's Alex deLarge lives on to sin to his heart's content. Even at his darkest King seems to insist on a reassuring order to things. Even as overwhelming a dark and nefarious elemental force as the one at the center of It is eventually banalized into the form of a giant spider that can be attacked and killed once and for all. We never know what is behind the grisly machinations of Kubrick's Overlook, and so we cannot ever hope to truly wrap our brains around it. [Footnote about burial ground, colonialist violence – the great lie at the heart of America?]

The other fundamental difference between the two authors and, consequently, the two works is that where King, for all of his leaps of imagination, is interested in explaining and literalizing and grasping, Kubrick has no interest in explaining. For him the mysteries of the Overlook, as those of any potential life beyond this one, are unknowable. Rather than tether its horrors to the neutering imagery of prohibition gangsters and the like, Kubrick allows the hotel's demons to retain their dignity by keeping them abstract and implacable. It is that staunch resistance to define the forces at work, to explain what's going on within those walls, that engrosses and repels viewers in equal measure. The reason the film is so consistently frightening is twofold: 1) the source of the terror is never truly explained, only suggested and hinted at, and 2) it burrows deep into the soul of a man to find only violence and rage. Even though the ending of the film is arguably a happy one on almost all fronts5 - except, of course those involving kindly chefs - we are left unsettled because Kubrick refuses to give us the comfort of answers. He's not interested in them. We are left to fill in the blanks with our own experience and conclusions. It's a hallmark of all of his films and the reason that he stands above all as perhaps the greatest artist in the cinematic medium.

People like to refer to Kubrick's films as impossibly complex and hard to understand because, I think, they feel it precludes them from doing the work to really engage with them. The truth is that, with the exception of 2001, Kubrick's films are very easy to follow from a narrative standpoint (even that one tracks pretty clearly – it’s really just missing some connective and explanatory tissue). It is the sub-textual elements, the arguments he is building from scene to scene, the density of his semiotics and the equal parts chilling yet thrilling effect of his shooting style, pacing, and sound editing that makes them complex. Robert Altman often said that when he was choosing scripts, he preferred to go with the simplest stories possible, so that viewers could follow the main thread of the plot with little to no effort while he was free to play around in the margins of character and behavior. The same applies in a sense to Kubrick. who often spoke of preferring stories with very clear, uncomplicated structures. The plots are usually threadbare, but the meaning behind them is elusive. What makes them so rich is the way he approaches them. If you read his scripts, you find that they tend to be almost completely devoid of stage direction - just dialogue and the bare minimum of necessary cues. Kubrick worked tirelessly to get the essential structure of his stories set, and once it was everything was free to be figured out and discovered once cameras were rolling.

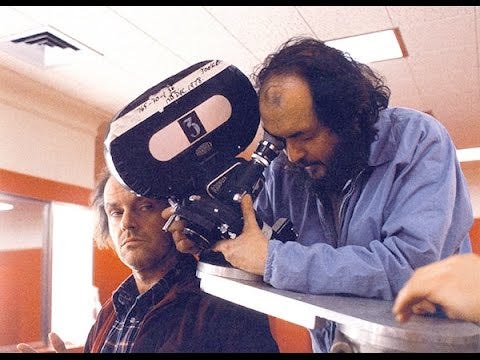

One of the great misconceptions about Kubrick was that he was a perfectionist, demanding take after take out of his actors until they gave him exactly what he wanted, when indeed quite the opposite was true. While he was tirelessly attentive to every single detail of his shot composition and mis-en-scene, he didn't come to set with storyboards. A photographer since childhood, he rehearsed scenes until he figured out which ways he wanted to shoot them and then placed his camera. While he would indeed record anywhere from 20 to over a hundred takes of any given scene, it was not because he was pushing his cast to some ideal he carried in his head (no filmmaker who was that inept at communicating what he wanted would last very long), but rather because he had no ideal. In A Life in Pictures, the appropriately exhaustive (and excellent) documentary about his life and work, Malcolm McDowell explains that while working with Kubrick on Clockwork, he asked the director for the secret to his technique, and that the reply was that he had no idea what he wanted. Sydney Pollack tells a story later in the same documentary about filming a shot of him walking across the room to open a door that took an entire day to shoot. If Kubrick needed a shot of someone walking across a room, he wanted every possible variation of that character walking across that room that he could possibly get so that he could choose which was most appropriate in the editing room. An exhaustive researcher (this is the man who wrote individual index cards each accounting for every single day in the life of Napoleon Bonaparte for a movie that never even happened), Kubrick shot a movie just as he collected data. He wanted every single piece of information on any given topic that struck his interest6.

And ultimately, whether King likes it or not, that's exactly what a good adaptation should be - something that takes either the fundamental structural pieces, or certain fundamental characters/pieces, of a pre-existing work and re-purposes them in the service of a new medium while filling in the gaps with the adapting artist's sensibilities and still managing to make a concrete dramatic, thematic, or emotional point that works within the context of that new piece on its own. Sometimes that's in line with the author of the original work intended, but often it is not. And that's understandably frustrating for the author, especially when the work is one that is by all accounts so close to his or her heart. And yet, if an artist isn't given free rein to craft something as potentially different as the thrilling and cinematic experience of Kubrick's The Shining, then we run the risk of being subjected to superficially faithful yet unremittingly turgid product such as Mick Garris' King-scripted and overseen The Shining. As someone who has watched with horror as the seed of his original idea has been mangled into something hideous and unrecognizable, I understand where King is coming from, yet as the author of Pet Semetary should know all too well, sometimes the best thing to do is let go, especially when the original work remains untouched.

- cs

For further reading on The Shining, check out my brother's excellent piece on the film as part of his Great Moments in Cinematic Drinking series.

The only theory about the “true meaning” of the film that holds any water for me, in fact, is the one that posits that it is about the genocide of Indigenous peoples - the hotel is decorated in Native American art, and they even have the “Indian burial ground” reference during Ullman’s tour - though even that misses the mark somewhat as the film seems to be about the destructive nature of white male violence in a more general sense (the only murder we see in the film is of Halloran, a black character, who lives in the book; note how Grady, the ghostly waiter who murdered his entire family when he was both alive and the previous caretaker before Jack, drops the n-word when alerting Torrance to his imminent arrival at the behest of Danny, who has connected with Halloran due to their shared psychic abilities).

The Shining may in fact be the ultimate representation of the all-consuming nightmare of writer's block. Anyone who's ever panicked over the endless expanse of a blank page knows all too well that suffocating feeling elicited from the paradox that, the longer you struggle over your work, the more time you're wasting not getting that work out there. The resulting existential conundrum so paralyzing to writers sure as hell feels like being trapped in a geographically impossible, labyrinthine hotel that more and more seems to represent a twisting descent into your own dark consciousness. And by the end of the film, Torrence has achieved the ultimate aim of any writer - he has transcended the bounds of his earthly existence and lives in a place of perpetual fantasy.

We also know that Kubrick had what could be interpreted as mixed praise for King’s work. In a 1980 interview with Vincente Molina Foix, which can be read in The Kubrick Archives, he says that the novel was “very compulsive reading, and I thought the plot, ideas, and structure were much more imaginative than anything I’ve ever read in the genre. It seemed to me one could make a wonderful movie out of it,” but later says that “He doesn’t seem to take great care in writing, I mean, the writing seems like if he writes it once, reads it, maybe writes it again, and sends it off to the publisher. He seems mostly concerned with invention, which I think he’s very clear about.”

Duvall's is a performance that is similarly maligned, though for very different reasons than Nicholson's. Far from being the weak character that many would peg her as, Wendy is every bit the long-suffering wife of an abusive husband, constantly explaining away his outbursts to herself and others (let us not forget that in order to be a strong character one does not have to literally embody strength, but be fully-fledged, multidimensional, and believable given the context of the film). Duvall's representation of a woman pushed to the absolute psychological limit is nothing short of masterful, and anyone who disagrees is likely assuming that they would react any better to some of the more outlandish events that she is forced to endure. Or, frankly, a little sexist - there is a tenor to the way that some people refer to her in relation to this movie that is similar to those who rail against the wives of TVs great male anti-heroes of recent years. There are a lot of people who likely enjoy The Shining on the level of wanting to watch Jack be Jack at his psychotic best (to be fair, one of the film's many delights), and I think they tend to see Wendy as standing in the way of allowing him to become the fully unhinged personality that they want him to be (and also, given the well-reported difficulties between her and her director, of standing in Kubrick's way as well). Duvall is one of the great screen presences of the 70s and early 80s, and her performance here is way too often overlooked.

Seriously. Wendy and Danny escape, now free of the man who has stood abusive watch over their lives; the ultimate evil has consumed itself and can no longer reign over them. Meanwhile Jack, while dead, lives on as the ghostly master of ceremonies in an eternal party, frozen in time at that 1920s New Year’s Eve Party, with the only genuine smile we have seen on his face for the duration of the film, arms open in a warm gesture of welcome, free to live as himself at last.

Part of the reason that Kubrick's films are so rich and so enduring is because he drew inspiration not only from films but from everything - literature, painting, science, Freudian psychology, advertising. In speaking of The Shining, for instance, he explained the lack of expressionistic architecture and lighting as an attempt to emulate the way that Kafka wrote - portraying surrealistic occurrences with the detached prose of a journalist (something that hasn't even been successfully achieved by those who have literally adapted Kafka's work for the screen, who usually opt for visual techniques that are just as surreal as what they are recording).