Luis García Berlanga: Working Under Fascism

When you live under an evil regime, being a bad countryman is the highest honor

I’ve been thinking a lot about authoritarianism lately. Now that we are living in the dawn our own inevitably low-rent, dime-store version of all-out fascist autocracy in America after the slow creep of previous decades, it becomes contingent on any citizen with a conscience to look to the myriad ways in which people of the past have not only rebelled openly against evil systems of totalitarian power, but also the smaller ways in which resistance is able to be carried out - sometimes completely in the open.

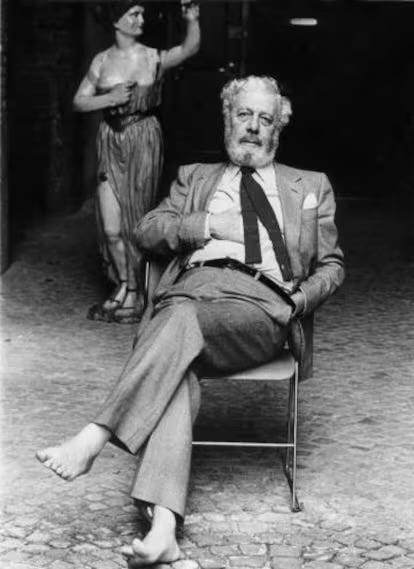

Luis García Berlanga was a writer and director who spent the majority of his career living under and working within the strict censorship of the Franco regime in early twentieth century Spain. Franco’s dictatorial rule was characterized by a projection of moral certitude under the guise of nominal Christian and family values and yet was attained and maintained by violence, oppression, and murder. The fact that someone like Berlanga was able to make films that were scathing indictments and satires of life under Franco’s fist is something of a miracle, and is certainly a model to look towards in today’s American climate - though it seems unlikely to be replicable in a media environment that has completely capitulated to and normalized Trump…or seems content to pretend like nothing all that bad is happening.

Berlanga was able to dodge Franco’s censorship in part through the subtlety of his wit, even as his satire is so pointedly aimed at many of the day-to-day horrors of life under Francoist rule. And yet Franco was aware to a degree of what Berlanga was doing - when one of his subordinates branded the filmmaker a communist, the dictator shot back that he was “something worse - a bad Spaniard.” Perhaps Berlanga skirted by because comedy is taken less seriously than drama and can be more easily dismissed as poweful critique by those who have no interest in hearing what it has to say - no point in stifling a message that would already be seen as dulled by the palliative force of humor. According to the BBC the films actually were suppressed somewhat, and Berlanga never really found that large of an audience within his own country until after the dictatorship had ended (perhaps because his countrymen finally felt like it was finally safe to laugh at the horrors), though they were rather successful on the international festival scene - he won the FIPRESCI prize at Venice for The Executioner, was a regular presence both at that festival and at Cannes, and Placido received an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. Of course, we also know that past a certain point it was surprisingly easy to get one over on Franco.

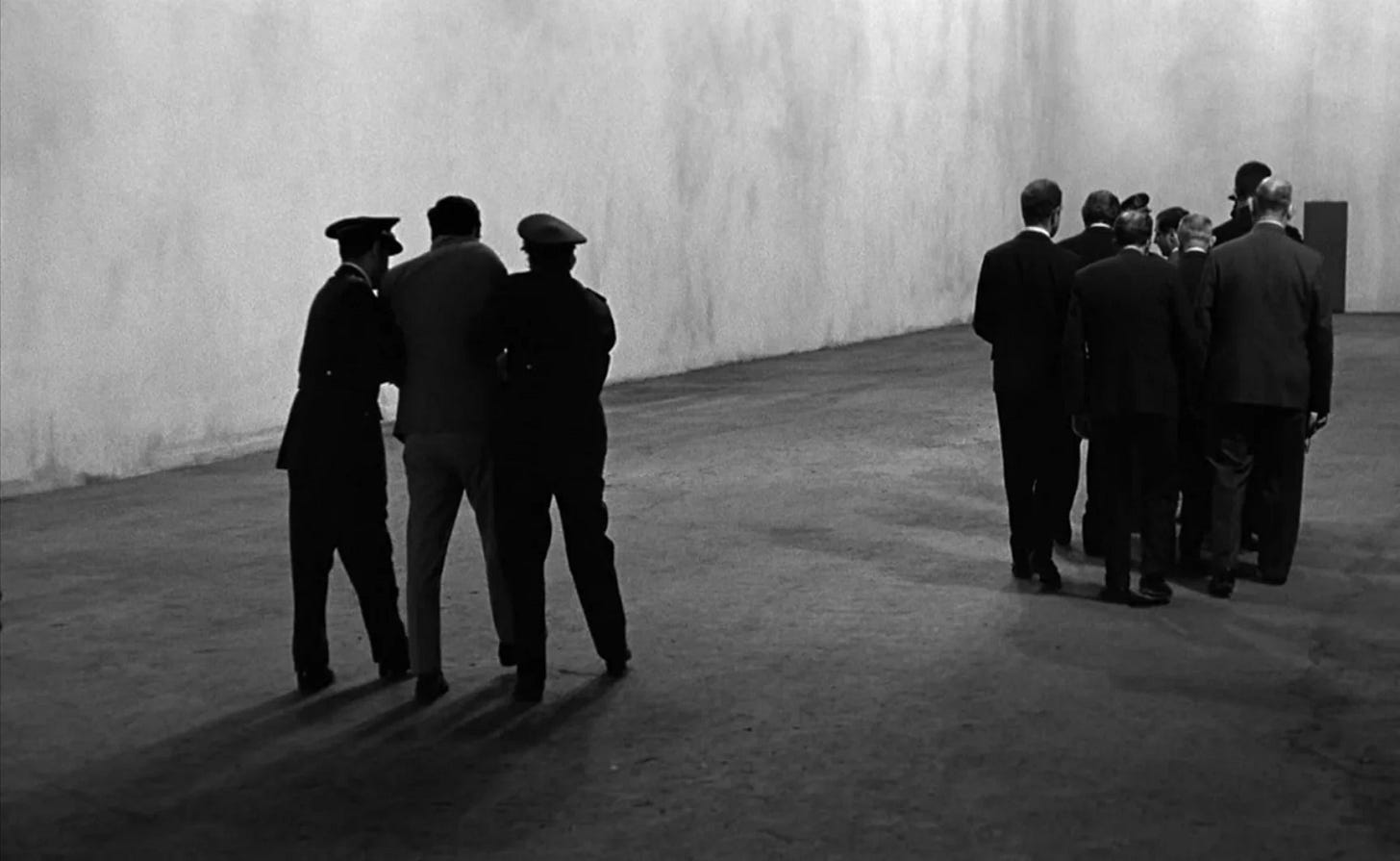

I discovered Berlanga when the Criterion Collection released The Executioner in October of 2016 (spectacular timing, that). I was struck by the cover art, and the screenshot that they used on their website for the film sparked something in me - the combination of that still image plus the film’s title inspired an entire short film of my own that was immediately complete in my mind. I sought out the actual film as soon as I could and loved it1, but wasn’t able to catch up on any his others until they became available on the Criterion Channel. A few years ago I tore through most of the ones on that service, and found a couple of others through alternate means. One of the first things I noticed was the continuity of so many of the stylistic elements that I had adored from The Executioner - the characters who were equal parts loud and heightened, drawing as Berlanga does from the Spanish literary traditions of caricature and the grotesque, and yet completely believable and fully realized; the extended takes, often building and developing in not just incident but volume - so many of Berlanga’s films play out in a series of long unbroken shots in which a host of actors fill and move through the frame, all talking over each other in a steadily building and yet carefully constructed cacophony; and of course, the scathing with that made the films always enjoyable even when they were confronting unimaginable horrors and bottomless human corruption and venality.

Berlanga is often mentioned along with Luis Buñuel as one of the titans of Spanish cinema - it’s basically them for the majority of the 20th century and then Pedro Almodovar picking up the reigns at the dawn of the 80s, right as Spain begins having free democratic elections once again - but the similarities go beyond just nationality. Like Buñuel, Berlanga eschews direct expression through camerawork or editing in favor of mise-en-scene, and both filmmakers have a scabrous yet subtle wit (though Berlanga gets much more outré towards the end of his career, once Franco and his censorship are no longer a factor). Those connections were always apparent, but what really struck me the more I dug into his filmography was how much he also reminded me of Robert Altman, with his sprawling ensembles and the coordinated messiness of his human characters. Berlanga’s framing is a little more precise than the constant documentary-style searching of Altman’s lens, and yet the messy and vibrant humanity within the frames, chock full as they are with their multitude of characters, is similar. You also see his influence, whether knowingly applied or not, in more recent fare such as The Death of Stalin or even Succession.

And yet he remains largely unknown in America. Almodovar, who has long sung his praises and who appears in a video interview discussing his importance on the Criterion release of The Executioner, has often compared him to Billy Wilder. That seems most apparent to me in Welcome Mr. Marshall!, an early effort Berlanga co-wrote with Juan Antonio Bardem about a struggling small town that activates itself when they learn that they will be visited by a group of American diplomats who are traversing Europe scouting potential recipients of funding as part of the Marshall Plan, an American initiative to help rebuild Europe after the devastation of World War II. Mr. Marshall is doubly pointed in the way that it depicts the efforts of the townspeople to redress and present themselves and their home as appropriately “Spanish” in order to best appeal to the preconceptions of their visitors, the efforts proving ultimately futile when the Americans drive as quickly as possible through town with nary a word spoken. The film sends up not only the condescending stereotypes through which America views other nations, but also comments on the underlying Francoist illusion of a “proper” Spain, an idealized projection of a country built on “family” and “Christian” values that hides the rot and corruption within and at its core. Because America is here the direct target of the ruse and the ultimate deliverer of disappointment and foiled dreams, however, the film is able to sneak its criticisms of its own country under the radar.

These Francoist values are further satirized in Miracles of Thursday, another film about a small town banding together to enact a deceitful attempt at enrichment - only this time, the scheme is to fake the appearance of a saint in order to draw in tourists and religious pilgrims, eager to witness the visions, whose presence will boost the economic health of the village. Miracles is a biting and effective satire until its second half, in which a mysterious stranger shows up in town and begins questioning and poking holes in the encounters that the townspeople have directed. The final reveal - that this stranger is in fact the saint whose presence the conspirators have been faking - kind of deflates the whole thing and feels like a resolution imposed by the state in order to ensure the film’s release. And yet the irreverence with which not only the film but the characters within treat even these phony miracles - they are always bickering and it’s always a giant pain in the ass - feels gleefully anti-authoritarian in its way. Even the title, with its indication of miracles as a scheduled, rote occurrence, helps make the thematic point.

Placido, which I’ve written about briefly before in this space, is perhaps the apotheosis of Berlanga’s stylistic traits and thematic concerns. The film is a withering critique and satirization of Christian charity - every year on Christmas Eve, the wealthy citizens of a Spanish city invite the impoverished into their homes for dinner. The recipients of the alleged good deeds are no more than pawns in the quest for their eternally self-absorbed bourgeois benefactors to secure a sense of self-worth and project a certain level of piety to their peers. The night is the subject of a constant live broadcast, the benevolent upper class argue about which type of poor person is better to have - someone who lives on the streets or someone who is elderly - and once the poor are of no use they are cast back to their dismal lives. The movie climaxes when one of the beggars suffers a heart attack, and the noble Christians decide they must get him to the house of his girlfriend so that the two can be married before he dies. They don’t bother to confirm just how committed the relationship is, nor are they much help after depositing his corpse in her living room and bidding farewell for the year. This is the film that exists most directly in continuum with Buñuel; released the year after Viridiana, it feels of a piece with that movie not only in its excavation of Christian hypocrisy but in its further evisceration of every single false projection of Franco’s Spain.

The Executioner deals more directly with capital punishment as it existed under the dictatorial regime - here the protagonist gives a ride home to a government executioner and falls for his daughter. He is later caught in their house by the father, having seduced her, and in fear of the professional murderer’s wrath agrees to marry her and take up the family business. He is assured all along by his new father-in-law that he probably won’t ever have to actually kill anybody, just remain on constant stand-by; meanwhile, he begins to learn that this gruesome position within the government is his key to a better life, as it gets him priority access to a new apartment of his own and every other material thing he could want, including a family. The film not only deals with the question of how one lives a life of upward mobility within an evil system without sacrificing their own morality (spoiler alert: you don’t), but also shows the ways in which these systems of power infiltrate everyday life and slowly ensnare and destroy at every level the people who live within them - not just physically, as in the case of the executed, but morally and emotionally in terms of those forced to carry out the deed. The film builds to an extended, blackly comedic set piece centered on the lead-up to an execution, an unbearable march toward the gruesome act filled with pleading, protestations, and tears - not from the condemned, but from the poor sap who must carry out his murder, who has to be dragged to the site more forcefully than his eventual victim.

By the time Berlanga releases The National Shotgun, Franco is dead, the dictatorship has been dissolved, and Spain is in the process of re-establishing democracy even as they are being ruled by a Franco successor as king. Power has been divvied among individual autonomous regions, and it is within this transitional period that the film takes place. José Sazatornil plays Jaume Canivell, a somewhat pathetic striver who pays out of his own pocket to organize a lavish hunting weekend for a group of wealthy aristocrats in order to curry favor so that he can get an in with their corrupt government connections and put himself in a better position to establish his electric intercom business. Try as he might, and with increased desperation, Canivell is unable to corral or navigate the various absurd circumstances and interpersonal conflicts that arise and develop over course of the weekend long enough to successfully plead his case, and ends the film having shelled out untold amounts of money he likely can’t afford just to go home with a handful of dead, rotting pheasants. By this point, free of the restrictions of Franco’s state censorship, Berlanga is free to portray the bourgeoisie in full grotesquerie. His films become more overt caricature at this point, as they also begin to be filmed in color.

This is even more apparent in Everyone Off to Jail!, which also features Sazatornil playing ostensibly if not literally the same character he portrayed in National Shotgun. Release in 1993, the film comes out deep into the post-Franco democratic era, and yet the dictatorship looms large. The story centers around a publicity stunt put together to honor former political prisoners of the regime by inviting them to have dinner and stay the night in the prison in which they were all incarcerated. Rather than an intercom manufacturer, this time Sazatornil is a toilet salesman who was indeed once briefly imprisoned and yet has only returned to seek missing payments from some of the other participants. The film, which was Berlanga’s penultimate and won Best Picture and Best Director at that year’s Goya Awards (the Spanish equivalent of the Oscars), is post-Francoist not only in its narrative but also in the way that it shows Berlanga further embracing the creative freedoms offered by a liberated Spain. The same burst of inhibition that springs forth from the early Almodovar films is present here as well - Berlanga’s style remains consistent while the content is pushed to further extremes - though the film also provides an interesting contrast in that Almodovar is at this point younger and more plugged into the current contemporaneous zeitgeist, while Berlanga’s film definitely feels at times like one made by an older man in ways that are fairly evident - particularly in its handling of sexual and gender identity.

A large part of why Berlanga’s films resonated with me so fiercely was not just their stylistic tenets, but the tonal balance they strike. Large and boisterous while also grounded and quietly devastating, they convey the absurd in a way that you don’t often see in cinema, where the exaggerations are often so immense that they push all the way into the cartoonish. Most social critical films, on the other hand, tend to go too far in the other direction of doing their best to replicate the staid and tragic reality of the worlds they are depicting, often to a point where they end up as hollow imitations of reality that completely defang their intended point or otherwise root themselves so specifically to a place in time or a cause that they are rendered obsolete even by the time they are release. Part of what ties Berlanga to the literary tradition as much as the cinematic one is that his films offer a level of critique and satire that you rarely get in film, as it is an art form that requires so many resources and so much capital at all levels, and is usually thus either connected to monied interests that have no desire to rock the boat, or tied to and at least partially funded by national governments - which in the case of a government like Franco’s would make it tricky to fund subversive work.

Which makes it all the more incredible that we got the films we did from him.

It has only been in recent years that the political dimension of Berlanga’s work has come into even more stark relief and has been centered more for me within the overall context, particularly the ways in which it was able to strike so directly at an enemy who was so powerful, so vengeful, and so unhesitant to enact vengeance on artistic figures he found to be in opposition to his aims. I’m not naive enough to think that films or art can save us in direct ways from violent state attempts at control and suppression - certainly not these days, when those things are increasingly commodified and devalued2. But I do think that they can do their work within people’s souls, even if that work is sometimes quiet and unseen. There’s also something to be said not only for the ways in which art can, in this particular context as in all others, give voice to specific and much-needed points of view and assure us that we are not alone, while also laying historic claim to the reality that there were people present who stood in opposition to fascism, while also presenting a template for potential acts of resistance and insistence in times where those forces rise again.

The cultural and historical record only wins out when the record is made in the first place.

-cs

While also feeling immediate relief that was dissimilar enough to my own premise that I was not inadvertently ripping anything off.

The victory of the corporate class in re-designating any and all creative endeavors under the conglomerated term “content,” combined with the tech oligarchy’s insistence on cramming AI down our throats (with little to no resistance from some of the people who stand to lose the most from its omnipresence) is a fight that I have been fighting on what feels like my own private island for this very reason, because this is one of the ultimate endpoints of such a campaign.