When I wrote abut Rhinoceros a couple of weeks ago, I discussed Martin Esslin’s Theatre of the Absurd and not only the impact it had on me, but the writers within its pages to which it introduced me. Of the three central figures discussed, I already knew Ionesco and Beckett; I was alos familiar with some of the other playwrights that Esslin highlights later on in the book such as Pinter and Albee. But there were plenty I didn’t know - Sławomir Mrożek, Dino Buzzati, Manuel del Pedrolo. Equally unfamiliar to me was the third component of Esslin’s primary troika, Arthur Adamov - credited as the first chronological writer of the absurd in that his first produced play predates Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano by 3 years and Beckett’s Waiting for Godot1 by 5. Adamov’s body of work, as so vividly described by Esslin, was thus a total discovery to me, and I was immediately fascinated and desperate to get my hands on as much as I could.

That proved to be no easy feat. I managed get a used copy of an anthology that contained Professor Taranne, a short work of nightmare logic in which the titular figure defends himself, with increasing futility, against charges that he exposed himself on a public beach and which ends in the complete dissolution of his identity. But that was really the only piece that was readily available in any form, no matter how many used book stores or web retailers I scoured. To this day I even check the start of any drama section I come across hoping to find some heretofore undiscovered anthology, to no avail. I even pored over the booksellers’ carts along the Seine when my wife and I visited Paris in 2018, but still came up empty-handed.

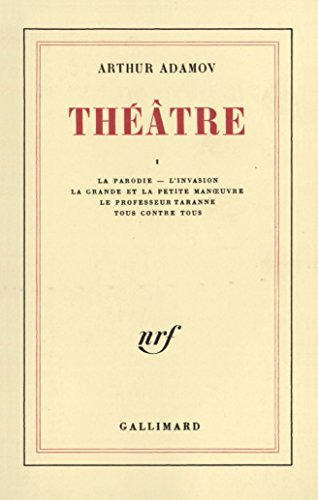

It wasn’t until 2020, when Covid lockdowns hit and the Internet Archive’s expanded access to its loanable materials inspired me to take more advantage of what it had to offer that I realized the resource I had there. And indeed I ended up finding digital copies of an avant-garde anthology containing The Invasion, in which the struggles - and failures - of a translator over how to best preserve the original work of the unknown author he is transposing are expressed by the striking image of a growing pile of papers that take over the entire stage; also Ping-Pong, in which two men’s lives become taken over in multiple ways by their obsession with a pinball machine - in which a small ball bounces indiscriminately around the cabinet of a pre-designed landscape, hoping to score points for the player who has the illusion of control given by two small flippers - in a work that is not only an examination of our over-dependence on technology but a questioning of whether we as humans in a mechanized, structured society actually possess the free will we claim to treasure (a frequent theme of Adamov’s). Both of these were available in English translations, and yet the only copy of Adamov’s first play, La Parodie, collected in the original chronological publication of his works, was only available in the original French.

Ever since reading Esslin’s book I was struck by his descriptions of this first work - both of Adamov’s and potentially of the Absurd. Its stage setting in which the scenic elements remain the same and yet are re-configured from scene to scene; its secondary characters who swap themselves out with new actors who perform the exact same roles; the handless clock that looms over the proceedings while the characters ask each other for the time, and under which the character of N. lies throughout the action, supine and defeated; the once-again recurring theme of human beings stuck in modes of living and communication that they are beginning to suspect are meaningless and yet which they are nonetheless helpless to escape, all accompanied by the sonic landscape of a police state with its constant police sirens and ghostly interrogations piping out from backstage. I wanted to know specifically how this all fit together and played out. And so while I was excited to have found it at last, I lamented that it had never been made available in an English translation.

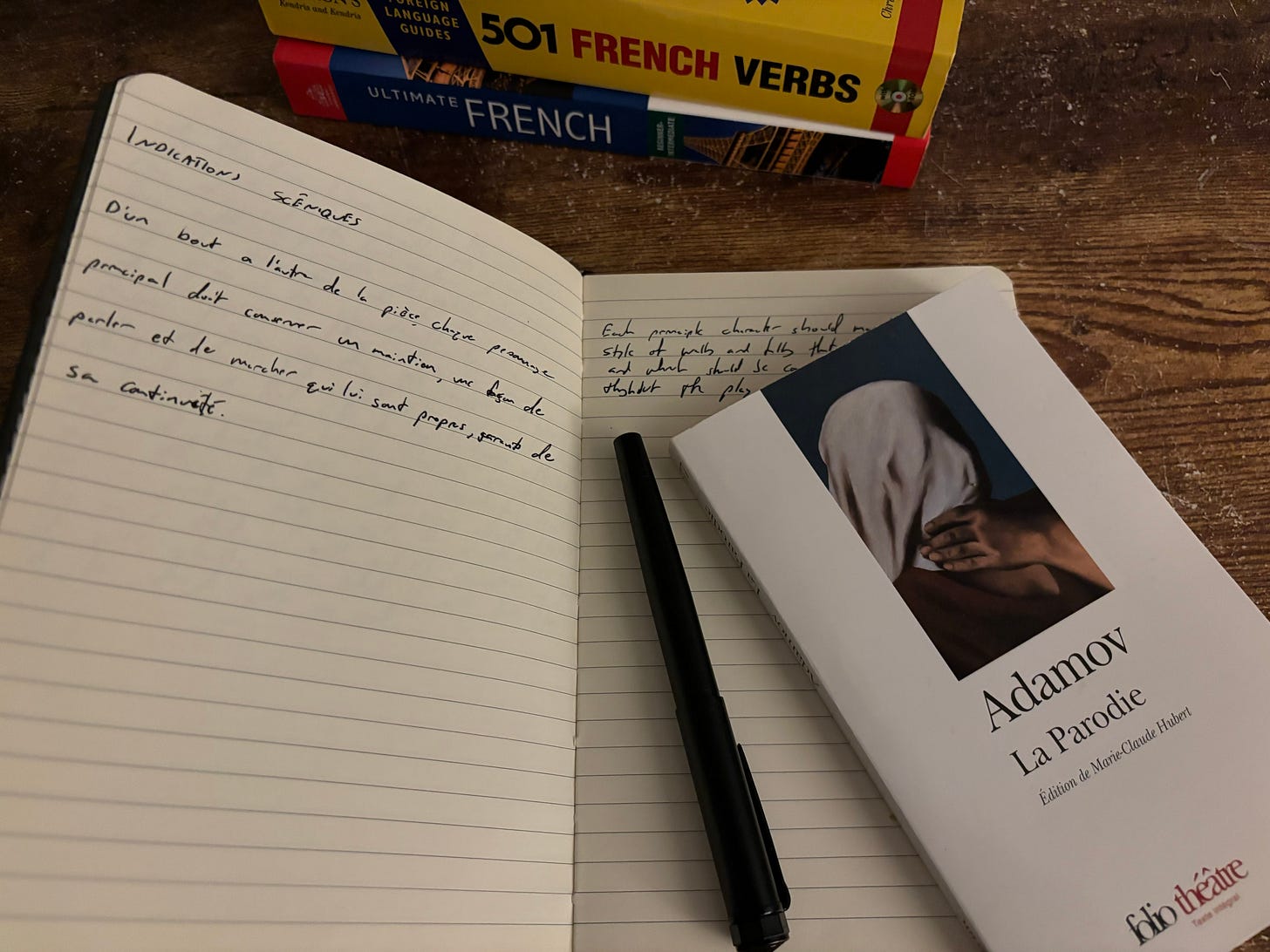

This initial discovery being made during Covid times, and me thus having nothing but endless free time and a growing sense of anxiety and doom that needed to be suppressed, I decided the only reasonable option was to translate it myself. I knew a little French from four years of study in high school, enough to get by at least2, and certainly enough to get the basics while using any and all available resources to fill in the gaps. And that worked for a bit, but the project soon became daunting and as the lockdown dragged on I, on the one had, sought less taxing methods of filling time but also plunged headfirst into preparations of welcoming our first child into the world. And so this particular project was shelved.

In the past couple of weeks, however, bolstered by my revisiting of Ionesco in the wake of finally viewing the film adaptation of Rhinoceros, I got the itch to dive back in. When I first started this endeavor I was working part-time, had no children, and was living through a pandemic whose socio- and geopolitical implications not only had me questioning any meaning within existence but also made it seem like society as we knew may have been on the brink of ending. Now I have two young kids and am heading into a fall semester in which I will gratefully welcome the additional burdens that come with a tenure-track position. I have also been brought on to co-author a textbook on screenwriting (more on this later, perhaps). All of which together grants me little free time. And so obviously, a perfect time to take back up a hobby that promises to be not only time consuming but intellectually taxing. And while I have also come to a point where I am grappling with something far more intimidating than a cold and uncaring existence - a universe that may in fact contain meaning. And yet it’s also never been clearer, in the geopolitical reality we now face, that this meaning - whatever form it may or may not take - is one that remains elusive to most of us, through forces both within and beyond our control, and also through our fundamental inability as a species to see each other as human beings with our own desires, identities, and senses of interiority. Without reflecting on it too consciously, it is perhaps for this reason that the absurdists in general, who have always appealed to me both aesthetically and thematically, and Adamov specifically - one of the more politically-minded Absurdists, he transitioned into more socially-realist works later in his career - have been at the forefront of my mind recently, as they give us a model of how to reject existing systems in order to not only address the changing nature of our times but also create something revolutionary and new.

But even more to the point? I want to be able to finally read this play. As I progress through this endeavor, I hope to use this space to write further about the process and perhaps post some samples of the work. I don’t know what the copyright situation is, and so I probably can’t post much of the text. I’m doing this completely on spec (insane).

In addition to various language guides that have already proven essential in filling in the bits and pieces that sail past me, I am also indebted to the few scholars I’ve been able to find who have actually written about Adamov in English - in addition to Esslin there is John J McCann, who published what seems to be the only American monograph on Adamov’s work - for the ways that they have helped me to contextualize his work and get a sense of his style and worldview, as well as to the actual professional translators who have carried his other works across the Atlantic. My pitiable attempt to follow in their footsteps should in no way be taken as an indication that I am equally-qualified.

Now truth be told, I don’t know the first thing about literary translation - at least in terms of performing it as a process. I am an amateur in that regard, and nothing I say about any of this should be taken as a suggestion, even accidental, of any kind of authority. This is simply the process that I feel is most effective for me, and which gives me the clearest path through this lunatic undertaking. What I’m doing is first reading through the entire play in order to get the broadest of strokes (provided I read and re-read somewhat slowly and carefully). I am then taking it scene by scene. First, I transcribe the play text directly from the edition that I’m using in the original French. Doing this, in tandem with the original reading, allows me to internalize the rhythm and language of the work - even though I don’t understand it word for word3, and even though it will change somewhat in the translation, this is important. It all helps the original incarnation become a part of me, and the physical writing of it is like playing scales, or sight-reading.

At that point, I do one of two things. I either translate the scene word-for-word, in order to get the literal translation that serves in essence as a very rough draft, which will then be refined to flow better, more directly express the text in a different language, and in some cases modernize the text ever so slightly while preserving as much of its original intent and spirit as possible. It’s incredible how much of this skill I seem to have already developed inherently from watching subtitled films, particularly Spanish- and French-language films, as those are the languages I know best other than English. The real-time lessons in translation one receives when they can understand what’s being said while also recognizing how and why that become what’s been typed out onscreen is rather cumulative in its way.

If I understand enough of the original text, then I go more-or-less right to my translation, which is what I did for the opening paragraph of the scene description:

D’un bout à l’autre de la pièce, chaque personnage principal doit conserver un maintain, une façon de parler et de marcher qui lui sont propres, garants de sa continuité.

Which in my initial translation becomes:

Each major character should maintain a style of movement and speech that is unique to themselves, and which should be consistently maintained throughout the play.

One paragraph down, 61 pages to go.

Not the most complex piece of transposition, but even this little bit has me excited to continue, as it makes this whole thing seem more attainable. Though I expect the process to be very slow overall, and likely undertaken in fits and starts.

And what’s great about my chosen subject is that, even if my attempts are a complete unmitigated failure, I can just chalk it up to the inherently Absurdist notion that human beings, locked as we are within our own inescapable consciousnesses, are fundamentally incapable of communicating meaningfully with each other!

-cs

Beckett’s first completed play, Eleutheria, was set aside when noted French actor/director Roger Blin chose to instead mount Godot and while it had its first staged readign and was published in the 90s, it was not produced until 2005.

Unless you ask the barista at Du Pain et Des Idées in Paris, who rather impatiently corrected and clarified my pronunciation of “un thé,” a humiliation and shattering of my multilingual confidence that no amount of guttural r “mercis” could assuage from that point forward.

I cannot stress enough how insane it is to be doing this without fluency in French. But I also cannot stress enough how aware of that fact I am, and must reiterate that this is not a professional job but purely a writing exercise.