David Lynch Has Moved On

Saying goodbye (for now) to one of the most significant creative figures of my life

David Lynch died this week at the age of 78. Even typing those words feels so strange. I got the news as I was aimlessly scrolling Instagram at a red light; his official account had posted a statement from his family. My heart dropped - I felt that strange weight that always arrives with unexpected bad news, like you’re straddling a pit with some unknown force tugging you down towards its depths. I had to pull over in order to not only confirm that what I was reading was true, but also to collect my thoughts1. There had been a lot of talk lately about his health - we knew that he had severe emphysema (news of his retirement had leaked out only for him to immediately and strenuously recant same), and the recent wildfires had necessitated his evacuation from his Hollywood Hills home. Yet the news still came as a shock; I didn’t realize until I read it the degree to which I had begun to take his continuing presence as a given. He felt somehow immortal, an unshakable constant even as the years had chiseled his face into a slimmer but no-less-handsome visage and the cigarettes had taken their toll on his voice.

I’ve talked about Lynch a lot in this space, even when not writing about him or his work directly, and I’ve certainly talked about him ad nauseam in my personal day-to-day life. I introduced my wife to his quinoa and broccoli recipe, and to this day sometimes draw her ire when I set our kitchen faucet to spray mode in part because that’s how his was pouring in the famous video in which he makes it. “What David Lynch thing is this?” she has asked at least once in exasperated response to some new and specific habit. As a younger man I would often hold court/people hostage at parties and gatherings with my insistence that he was severely misunderstood even by some of his biggest fans, only to then explain in excruciating and exacting detail why I felt that was the case. When I was going back to grad school for my MFA, my dearest friends gifted me for my birthday that year a Moleskine notebook and a Blu-ray copy of The Art Life. Just this past semester, I was walking from my office to make tea when a student stopped me to mention that they had just watched one of his films. I settled in and mentally cleared whatever less important things I was originally going to do that afternoon before class because I knew that, since the topic of Lynch had come up, it would not, could not, SHOULD not end anytime soon.

How do you adequately convey the impact on your life of someone that you did not know personally, and yet who was nonetheless responsible for so much of how it turned out? I always loved movies, but did not think of film as a serious art form until my later teens, when I started to see more challenging and interesting films including, most notably, Mulholland Drive in October of 2001. It changed my relationship to the medium and in effect the whole course of my life.

I’ve written of that experience before. Rather than try to sum it up, I am going to quote that piece here in its entirety - not just because it describes my proper introduction to Lynch and his work, but for the way it sums up my relationship to it:

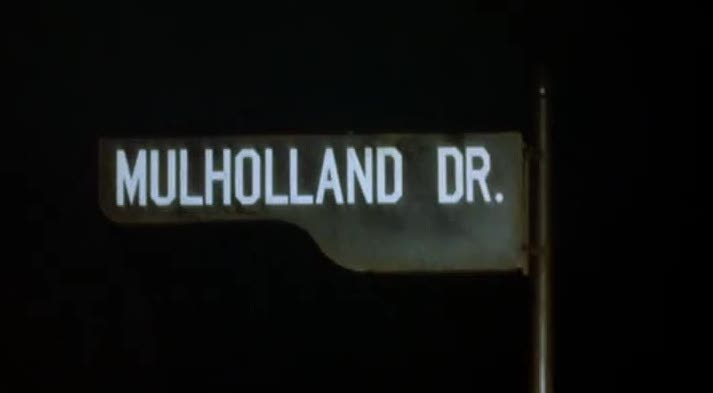

The Movie That Changed My Life: Mulholland Drive

I turned 17 at the end of 1999, which has for the two decades since been held as the last all-time great movie year by those who, like myself, came of age during that period. Indeed, that year saw the release of some monumentally important films as well as the debut/confirmation of just about every major filmmaker of the era. Spike Jonze, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, David Fincher, the Andersons Paul Thomas and Wes, Alexander Payne, David O Russell, Sofia Coppola, and many others all released debut or career-defining features. Older masters like Martin Scorsese, Mike Leigh, Pedro Almodóvar, and Michael Mann produced late-period masterpieces in filmographies that were already legendary. In an almost too-literal passing of the torch to the next wave, Stanley Kubrick finished his final film and died within days. Epochal as this year was, and as much as films such as Magnolia, Being John Malkovich, and Topsy-Turvey primed the pump for my appreciation of more non-mainstream or off-kilter fare, it was for me ultimately a prologue to the film that two years later would forever change my conception of what a movie could be.

I knew David Lynch primarily from reputation and as a shorthand for “weird.” I had read and absorbed enough through the culture about the content and impact of Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks to have a more-or-less keenly developed sense of who he was as an artist, but the only film of his I had seen at that point was The Elephant Man, a (fairly) straightforward historical biopic for which he received his first Academy Award nomination (in a genuinely crazy statistic, the other two nods possess the rare and record-breaking feat of being the sole nominations for their respective films). Which is to say that I knew generally what to expect, and yet was also ideally unprepared for what I was in for when I sat down with my brother and some friends in a mostly empty multiplex theatre to watch Mulholland Dr. What unspooled over the next two-and-a-half hours was a story of love, obsession, jealousy, deferred dreams, revenge, guilt, and heartbreak that was unlike anything I had ever seen. A personal tragedy that was also a statement on the predatory relationship between Hollywood and young starlets. A film that celebrated Los Angeles as a factory of dreams spun from the shattered hopes of those it lures and destroys with its promise of fame. A celebration of the beauty and catharsis of cinematic storytelling that at the same time managed to excavate the darkest corners of the human soul.

I came out of the theater that night not entirely sure what to make of what I had just seen but knowing that I had experienced something that was going to be a part of me forever. To describe the narrative would be both simple and impossible. To know what happens is to know nothing about the experience of viewing. For nearly two hours we’re told one multi-character story that, while spellbindingly aloof and dreamlike, is nonetheless straightforward until it suddenly turns in on itself in its last act, “the characters start[ing] to fracture and recombine like flesh caught in a kaleidoscope,” as Roger Ebert put it so vividly in his review of the film. Everyone we’ve gotten to know and care for, every character whose struggles we’ve been investing in is suddenly transmogrified into a different being entirely. The love that we’ve watched develop between Naomi Watts’ Betty and Lara Elena Herring’s amnesiac Rita, so pure and so delicate, so joyous in its eventual expression, has suddenly become a toxic relationship curdled by betrayal and bitterness. It all ends with Betty, the aspiring actress who for so much of the film has represented a stalwart optimism, a beacon of unbroken spirit, utterly destroyed emotionally, psychologically and, finally, physically. If it seemed cruel and unfair that what we thought the film was could change so suddenly, that the promise of the first part be so violently broken by its ending, then so too is the pain of lost love or shattered dreams; so too can be the moment we realize the true distance between fantasy and reality, between who we see ourselves as and the more uncomfortable truth of who we truly are.

Why then, with an ending so devastatingly sad, did I leave the auditorium in exaltation? Why was I convinced, even though everything in the story was only barely hanging together on a literal “What happened exactly?” level, that I had what I had just viewed was nonetheless a masterpiece? I spent days upon weeks upon months trying to put together the pieces of the puzzle and reconcile these and the film’s other myriad contradictions before finally conceding that the answer lie in the ambiguity. Appropriately enough, it was in that yielding that I was finally able to decipher the film’s mysteries, though of course there is always more to unpack and examine and question (on each of the above counts, Lynch the Buddhist and TM proponent must be appropriately satisfied).

It taught me the seemingly paradoxical lesson that a movie didn’t have to make sense to mean something while also affirming that the power of cinematic narrative and structure was so unshakable that as long as the individual components had emotional resonance they didn’t need to add up in the way we are conditioned to expect them to. It meant everything and nothing. It was without coherence and yet, of course, it ultimately makes complete sense. It is a movie that gives you just enough to be able to figure it out for yourself if you want to, but within which you can also get lost and wander around aimlessly and still get a complete experience. In short, it is a miracle; even more so considering its origins as a rejected and abandoned television pilot given new life via a burst of inspiration and the funding of a French film company.

It was the first time a film had worked on me in the same way as a piece of music, where I couldn’t necessarily articulate why I was feeling what I was feeling, but realized it also didn’t necessarily matter because what had been communicated was an emotional state of mind. One of the primary goals of any artistic endeavor is to translate subjective experience, to pluck from the teeming mess of our brains something that we can not only make concrete but share with the rest of the world in a way that they will understand and perhaps even be able to relate to. In doing so, we ensure that we are not alone. I had often experienced this with literature, which can more directly transcribe and intellectualize thoughts, ideas, and feelings but rarely with cinema. Until this moment. Because Lynch is able to so effectively utilize the language of dreams (not just cinema as a collective dream, but the actual rhythms through which our brains process and catalogue all levels of our daily physical and mental experience), he creates a cinema that is more direct in its abstraction than the simulacra of reality that is too often the goal of more “serious” films. Cinema had transcended the mere replication of reality from its earliest days – Georges Méliès pioneered optical effects that enabled literal magic to transpire onscreen, and the Soviets had by the early twentieth century advanced editing techniques that strove to liberate the form from the shackles of ethnography – but in the fall of 2001 this was all news to me, and it was like discovering for the first time that food could be delicious and enjoyable, could serve an experiential purpose beyond mere sustenance.

Going forward, and also looking back on films I had already seen with newly-opened eyes, my relationship to the medium was forever altered. It was a gateway to my understanding of film as a form of artistic self-expression in addition to being merely entertainment. It paved the way for me to discover more outré and left-of-center filmmakers like Luis Buñuel, Pedro Almodóvar, Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and countless others I cherish to this day and who even though I would have found eventually I may not have been set up to appreciate as fully. It deepened one of the core obsessions of my life while also blessing/dooming me with the unshakable purpose of chasing the high I felt that night, either through creating works of my own that were in some small way able to measure up, or by sharing that passion with others or enabling them to find their own means of expression. It’s a film that sits perched upon my shoulder, with an admittedly large and ever-growing host of others, every time I write a slug line or set up a shot. Whenever I teach a class, I ask myself whether what I’m giving my students is best enabling them to not only be open to a similarly ecstatic experience, but to also create work that will pass those experiences on to others. It’s a dark, frightening, beautiful maze that I disappeared into 19 years ago, and one which I’ve been avoiding the exit from ever since.

I became instantly obsessed with the film and with Lynch. I spent hours on the Lost on Mulholland Drive website (which still exists!), with its legions of screen grabs and theories; I played the soundtrack on repeat for the next five years; I wandered the UGA campus at night, loopy from the pain medication I’d been prescribed after my first sinus surgery and brainstormed my own lamentable knock-offs of Lynch’s vision. When it played at the campus theater I dragged my friends to see it, and I harangued them over its Oscar prospects that year, particularly for Lynch and Naomi Watts’ all-timer performance. Lynch would ultimately get a nomination for his direction, the second time he was the sole nomination for his film after Blue Velvet - a strange a wonderful record that I don’t imagine ever getting matched2.

I began to catch up with the rest of his films, though at that point it was still fairly difficult to do to completion. Blue Velvet was next, but Wild at Heart and The Straight Story were not readily available and Dune remained a mystery to me. I rented a widescreen VHS of Lost Highway and watched it alone that Halloween night. My true white whale at the time was Eraserhead, which was almost impossible to find. Lynch had released a DVD copy through his own personal website in 2000, but I was not in a place where I could justify spending $50 plus shipping on a single film, so I relied on the worn tape that was available at Vision Video in Athens (a mainstay for me in those years and an institution that when all is said and done may have had the biggest impact on my development as a cinephile). It was so old, and the tracking was so bad, that the opening ten minutes or so were completely illegible. But it didn’t matter; I was transfixed nonetheless.

It was from that same video store that I would eventually rent the pilot of Twin Peaks, which was not included on the initial Season 1 DVD set. I had to order season 2 on individual tapes piecemeal via eBay for the next several years. Wild at Heart eventually got a DVD release, as did a more affordable version of the Eraserhead disc. I was so excited that I talked it up to my then-girlfriend for weeks. When we finally watched it she turned to me in horror and asked, “Why in the world do you like that?”

It was around this time that I started to read rumors of a new Lynch film, his first in the five years since Mulholland Drive. I would prowl message boards and exclaim to barely-interested friends that he was shooting bits and pieces of some mysterious project in Los Angeles and Poland. When Inland Empire finally came to Atlanta as part of its four-walled touring release, I dragged a group of friends to see it. Just about every one of them hated it.

I didn’t much like it after that first viewing, to be honest, though I’ve now come to think of it as a fairly exceptional work, the digital photography dovetailing with Lynch’s obsession with fractured personalities to give a fairly prescient look at how the digitization of the world would rupture our individual and societal senses of identity. The methodology of its production - Lynch working with a skeleton crew and filming it bit-by-bit as he came up with ideas over the course of many years - also did more for the notion that the director’s camera is the equivalent of the writer’s pen than even the French New Wave filmmakers who originated the auteur theory.

Much has and will be made of the extent to which Lynch was able to give perfect expression to the inexpressible. Eraserhead is more than a movie about the anxiety of parenthood - it is very specifically about confronting the knowledge that to bring life into this world means that you are also creating someone who will at some point feel pain and suffering, who will eventually die. That’s a much darker thought than we’re usually willing to discuss when it comes to such a beautiful event as childbirth, but it’s honest. It’s a thought that has occurred to me that I have never heard anyone else express.

His films have resonated with so many in large part because was honest enough not just to portray the depths of trauma, and its aftermath, but also the ways in which it lives side-by-side with joy, with humor, and with the ridiculous and the banal. We do not get to compartmentalize these things in life, and so they do not get partitioned in his films. That makes them difficult for some to wrap their heads around, and it even makes some people very angry when they watch them. But it’s so much of why he was not only essential as an artist, but so influential. Tarantino and the Coen Brothers with their juxtaposition of violence and humor, profundity and inanity, do not exist without Lynch.

He was above all completely and utterly true to himself and to his own voice. This is another part of his appeal, especially to younger audiences. He was a figure of such immutable specificity and idiosyncrasy at a time in which our public personae are curated within an inch of their lives. He had a genuinely spiritual presence and placed a level of value on film as art in a way that seems extinct. But even beyond that, he was dedicated in full to the act and process of creation. He gave himself fully to any and everything he worked on and was just as happy to paint, make music, build furniture, or film goofy YouTube videos as he was to make a film. His entire life itself was one long and evolving work of art, and he wanted everyone to experience the kind of joy in creation that he received. That generosity of spirit extended to his work of raising awareness for Transcendental Meditation, and it infused even the darkest moments in his films; as grim as things could get, you knew that there was an empathetic presence behind the camera. It’s why no matter what his actors had to endure on screen, they all have nothing but the most glowing things to say about him. To work with him seems to have been a genuine metaphysical experience, just as to watch his films was to feel like you were digging beyond the surface of what art and life could offer and were plumbing heretofore unseen depths of feeling and expression.

One of my favorite scenes in his filmography is perhaps my favorite scene in the original run of Twin Peaks. It is the moment where we, the audience, having recently discovered who killed Laura Palmer, see the murder claiming their next victim. Cross-cut with one of the most disturbing scenes ever shown on television is a scene in the Roadhouse in which a number of characters have gathered and are listening to Julee Cruise perform. Agent Cooper has a vision of the Giant telling him that the killer is striking again, the old waiter with whom he interacted with at the beginning of the season as he lied on the floor of his hotel room bleeding from the gun shot that ended Season 1 comes over to offer an enigmatic apology, and then suddenly everyone in the bar begins to experience…something. A mysterious sadness settles on the crowd before the spell breaks and Cruise returns to the stage.

It is, along with the Club Silencio scene from Mulholland Drive, perhaps the key Lynch sequence because what happens onscreen is such a pure distillation and reflection of how we experience his work: a collection of people reacting with intense emotionality to something they don’t necessarily understand. The Peaks sequence is also illustrative in how it was made of Lynch’s fluid and open-to-the-randomness-of-the-universe process - Bobby is only there sitting at the bar because Dana Ashbrook, the actor who plays him, happened to be hanging out on set that day and Lynch, struck by inspiration, put him in the scene.

I knew that others had a similarly intense and meaningful relationship to Lynch and his work, and while the movie that did it for them often differed depending on the generation (for the originals it was midnight showings of Eraserhead; for many it was Blue Velvet or the original run of Twin Peaks; for those my age it was Lost Highway or Mulholland; for younger generations I have found that it is sometimes The Return or, in an act of rehabilitation that breaks the bounds of space and time in a suitably Lynchian fashion, Fire Walk With Me), the experience was the same as the one I describe above. How many artists serve that same purpose - opening up the idea of what their medium, of what art itself, can be - for successive generations with completely different and individual contemporaneous works?

Speaking to friends and browsing my feeds over the last week I have realized just how ubiquitous my experience was. But what a beautiful thing for such a singular voice to be so universal in its impact. What a testament to the power of his art, to his personhood, and to the very idea of listening to and following the music of your own heart no matter where the dance may lead you.

Just as Mulholland Drive was such a seismic filmgoing event when I was 18, watching Season 3 of Twin Peaks in my mid-thirties completely reframed my ideas of film and TV and of what I wanted to accomplish in my own work. It not only re-oriented me in a creative sense, but it even planted the seeds of a spiritual re-alignment that I’m still working my way through. I may frankly never figure it out, but if I’ve learned anything from his work as a whole and from The Return specifically, it is that the journey is what matters. Answers are not as important as questions, as the seeking. Questions open up portals between ourselves and the world, between us and other people. Answers close doors. Questions are about possibility while answers are about finality. It’s why I’ve been drawn to the abstract and the absurd ever since that night over 23 years ago; it’s why I keep coming back to his work and always will.

There was a sense, while watching The Return as it aired in the summer of 2017, that it was a summation of sorts of everything that Lynch had made to that point. It felt like it was all in there somewhere, that in addition to getting a sprawling canvas on which to paint every thought he had been working through for the ten years since his last film, that he was perhaps aware on some level that he would never get a chance to do something like it again. He was entering his 70s and had become rather non-prolific as far as filmmaking was concerned - nobody wanted to say it, but it seemed likely that it could have been the last major cinematic work we’d get from him. That has proven accurate. And while it may seem on the surface frustrating that the series, and his last major creative statement, could end on such an open-ended note of dark enigmatic dread - Agent Cooper stumbling around in confusion while the alternate-universe Laura Palmer screams in terror and the lights go out (in the Palmer house, on the street, in the world?) and the show cuts to black for good. Is there anything more, not just Lynchian, but absolutely beautiful and human than leaving as your last major statement a work that ends on a note of such irresolution, a scream of confused pain followed by a mysterious whisper that leaves viewers in a state of asking questions that we will never know or learn the answers to? Because it keeps us guessing and coming back. It lingers in the mind and on the heart, and it speaks in its lack of literal narrative finality to the eternal continuum of life on this planet even in the face of a momentary yet seemingly definitive conclusion.

Things may end, but they never die.

-cs

I have a strangely fully history of learning about the unexpected deaths of famous people while in cars - John Candy, psh.

You can hear the gaps in the nominations announcement video when the latter happens; one of them might be be screaming in joy from my dorm in Athens.