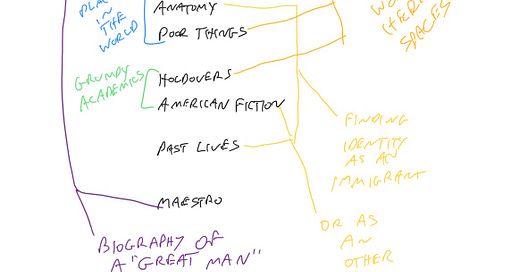

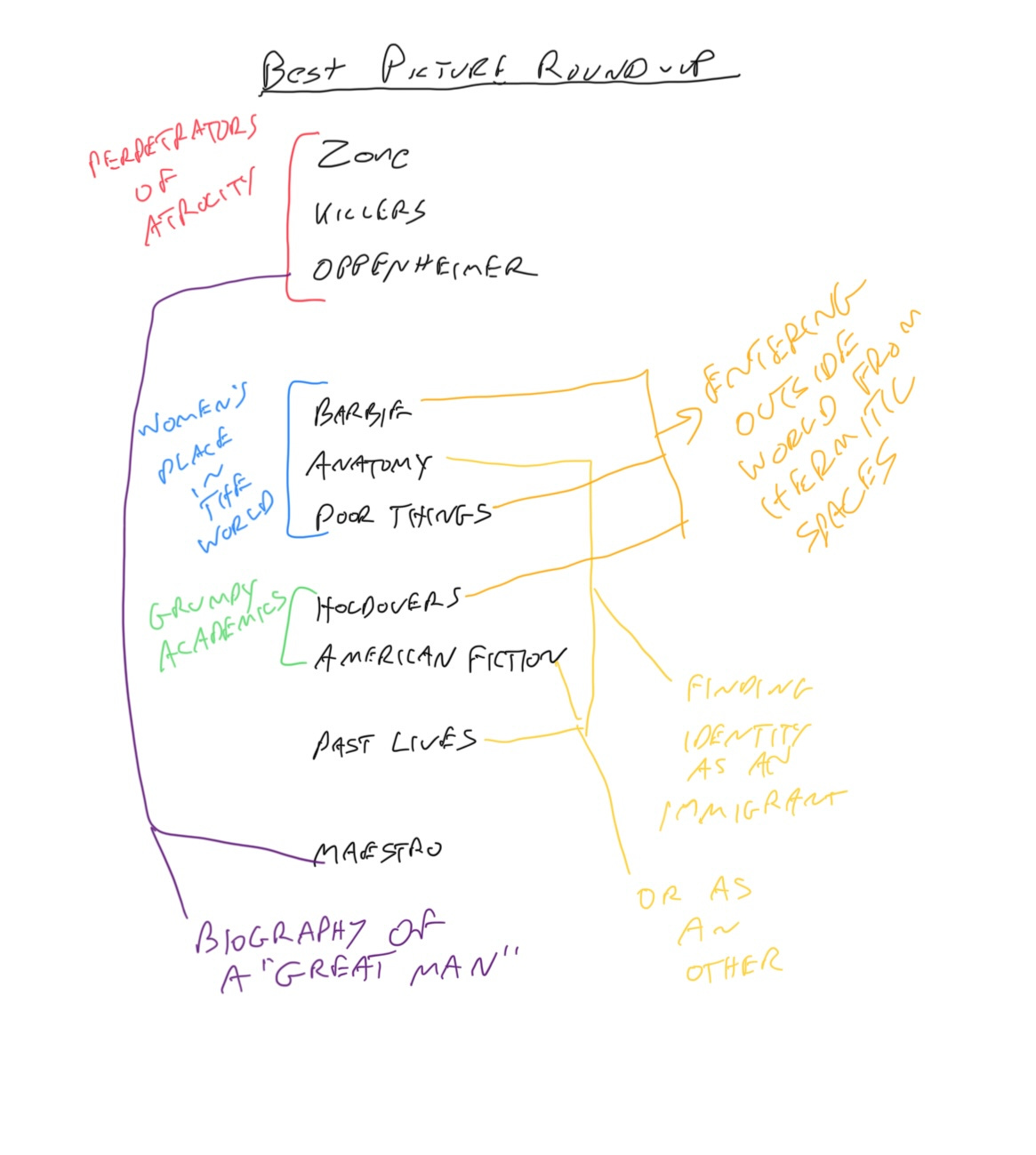

I have little interest in ranking or otherwise quantifying the films nominated for Best Picture, though I do like to consider not only their cinematic merits but also where they stand within the larger context of cinema/world history and what trends, if any, we can see playing out among their number. While much has been made of how strong this year’s crop of nominees is (a sentiment I don’t disagree with even as I wonder if it perhaps indicates of an overall parity with fewer outlying classics than other years), I think what’s most fascinating this year is how decisively one is able to group them neatly within sets of thematic concerns, with some branching out into even further sub-themes and categories.

Three of this year’s nominees - perhaps the most “serious” - deal with historical atrocity. The mass annihilation of civilian life by the first atomic bombs in Oppenheimer, the ruthless murder of the Osage people by white Americans in the interest of securing their oil rights in Killers of the Flower Moon, and the methodical extermination of Jews and other “undesirables” by Hitler’s Third Reich in The Zone of Interest. What’s fascinating is that each of these three films explores their respective atrocities from the perspective of those who committed or were responsible for them rather than the victims. Oppenheimer is the story not of the bomb but of its creator. By both design and dramatic intent the movie avoids directly confronting the horrors unleashed upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While I think this choice is ultimately justified by the film’s thematic interest in the idea of getting so caught up in an achievement that you can become blinded to the larger implications of it, there are nonetheless moments in the last hour or so where the repressed guilt over what he’s done bubbles to the surface and starts to rupture not just Oppenheimer’s consciousness but the form of the film around him; these moments have a visual and expressive poetry that the rest of the film lack, and I wish there were more of them as I feel like this is maybe the dramatic element of the movie that, other than the spate of woefully thin female characters (a Nolan speciality), is the least served of the whole endeavor.1

Killers of the Flower Moon takes the who’s-doing-this approach of the book upon which it is based and inverts that structure so that we are following events from the perspective of DiCaprio’s imbecilic Ernest Burkhardt, acting under the manipulation of his robber baron uncle King Hale as part of an elaborate plot to systematically murder the family of his Osage wife Mollie so that her family’s headrights can be legally made his. While I think this look at the willful blindness imposed by the dissonance needed to carry out such an endeavor against one’s own betrothed makes for a more interesting movie than the Birth of the FBI tale it would otherwise have been, I don’t know that it’s the most effective possible version we could have gotten. Part of the problem is that DiCaprio’s character is so dumb, and we’re so “in” on the plot as the audience even before he is, that it renders Mollie, otherwise so strong and so possessive of a piercing intelligence, borderline complicit in her own attempted murder for being so unable to see the signs of what’s going on right in front of her face. While she may be so desperate to believe that Ernest truly loves her, that’s not a case the film makes very compellingly as their relationship fell largely flat for this viewer. There’s also the possibility that Mollie has been so worn down by what’s been perpetrated against her, her family, and her people that she is darkly resigned to her fate; either of these possibilities would have landed more strongly had Mollie been framed more as the center of the narrative.

Of these three films, all of which I liked or admired a great deal, only The Zone of Interest really delves into the mindset of its perpetrators and expresses its ideas purely through form rather than psychology. I find this not only the most successful of these three in this respect, but the most artistically successful of all the nominees, for reasons I elaborated on in depth last week, though it’s worth repeating again that I think this is a once-in-a-generation piece of filmmaking.

It certainly doesn’t take much critical insight to note that Barbie, Anatomy of a Fall, and Poor Things are all about interrogating the place that women occupy in the world, though I think what’s particularly notable is that 1) we have three best picture nominees addressing that, each of which center their female character as the protagonist (it’s usually hard enough finding just one nominee a year that does this - and that's before even considering that Past Lives, which I’ll get to later, is also a female-led story) and that 2) each of these does so in such a different way that we end up with three incredibly distinct movies, ranging from the technicolor, studio-embracing aesthetic of Gerwig’s Barbie to the more rugged, hand-held immediacy of Anatomy, to finally the baroque steampunk absurdity of Poor Things. This is also, interestingly, the group that forks out to the most additional thematic subsets.

Poor Things, like not only Barbie but also The Holdovers, is about someone venturing from the comforts of a hermetic existence and experiencing the real world for the first time. Of course, in all three instances, the real world becomes a vehicle through which existential crises are navigated and self-shattering truths are delivered. Bella Baxter does what she can to bend the larger world to her own unique set of values. Barbie has to reckon with the spiritual ramifications of a world in which she no longer has any meaning. Paul Hunnam leaves the safe confines of a private boarding school only to be reminded of the failures that trapped him there in the first place. What’s of additional note is that, while in Poor Things Bella’s dissatisfaction with the world causes her to retreat back to a cloistered microcosm where she can rule supreme according to her developed sense of righteousness, Barbie and Hunnam both end their stories by making the sacrifice of choosing reality over safety despite the consequences.

Anatomy doesn’t just utilize its courtroom proceedings to litigate its protagonist’s womanhood (the question of her guilt in her husband’s death seems to also encompass questions of whether she was too cold with him, not nurturing enough of his perceived genius, too focused on her own career to be a worthy wife or mother), but also situates her as a German living and fighting for her freedom in a French courtroom. It is very specifically a story not only of how a woman is allowed to live her life in the world but of how an immigrant is allowed to frame their life within the larger context of the nation they have adopted as their own.

Celine Song’s Past Lives is similarly a movie that ties questions of nationality into questions of memory, identity, and relationships. In Anatomy the question is whether the court can extrapolate Sandra’s presumed marital sins to full-blown murder; in Past Lives the question is how much of herself Na Young left behind when as a child her parents decided to move from South Korea to Canada and she became Nora. The relationship with Hae Sung becomes a metaphor for the self that was left behind and with which, ultimately, she can no longer reconcile.

One can also tie this idea in with Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction as it is about someone trying to navigate the world as an other - in this case, a black man in America. The movie’s two-pronged narrative (Monk questioning his place in the literary community and also within his own family) provides a multi-level look at the idea of black identity. Monk finds himself pigeonholed as a black writer and academic, and lashes out by writing the book that he thinks white audiences want from him (which of course ends up being a success and confirming every ounce of his pre-existing cynicism); at the same time, Monk is trying to navigate his place within a family that he thinks doesn’t accept him - though in this case it’s because he has set himself apart by choice as a means of confirming his preconceived notions of who he is versus who they are. Monk is someone who automatically disallows people from accepting him, and the movie becomes largely about him overcoming his own self-defeating and self-alienating bitterness (Tiff said it was like an Alexander Payne movie written/directed by and starring black people, which is ironic since it has some of the acidity that the Payne movie it’s nominated against lacks). I don’t know that the movie fully resolves both of these threads - there’s a scene between Monk and another black writer who represents everything he’s trying to call out with his ruse, played by Issa Rae, that works well enough on its own but doesn’t quite click when taken within the larger context of the film - but it’s especially effective as a family drama, it has one of the more satisfying adult relationships depicted in recent memory. It’s also incredibly funny - there’s a reveal of not one but two RBG posters that may be the biggest laugh I had all year and which works as a perfect visual short-hand in a key moment.

Fiction also ties back to Holdovers in that they are both about grumpy academics who have to untangle their own issues in order to move forward, and Giamaiti and Wright both enshrine themselves nicely within the pantheon of Sad Professor Cinema.

That leaves Maestro.

Hugh Jackman voice: I didn’t see Maestro.

Just kidding, I saw Maestro.

It ultimately feels like something of an outlier here because its only tie to any other is that, like Oppenheimer, it is ostensibly a portrait of a Great Man from history. Like Oppenheimer, though, it’s a much more interesting version of what this could have otherwise been, though I think Maestro never really marries its dramatic interests to its formal ambitions. I’m reminded by its bizarre structure of an old Jim Jarmusch quote about how his version of a biopic would cut out all of the exciting portions of its subject’s life. That’s almost what they do here, though I don’t know if the intention was that pointed so much as a by-product of the chosen focus on Bernstein’s relationship with his wife Felivia Montealegre, played by Carey Mulligan. I will say that, in a year in which three Best Pictures were directed by women and four of them center female protagonists, Maestro is, like Flower Moon, a movie that would perhaps have benefitted from another script pass that shifted the focus even more squarely on its female lead.

And that’s part of why this Oscar year is so rewarding, so rich - even in the most otherwise disconnected film of the whole set, a connection!

-cs

Having now read American Prometheus it’s hard to separate certain elements I feel lacking with elements of the story and the person that I would have like to have seen emphasized a bit more