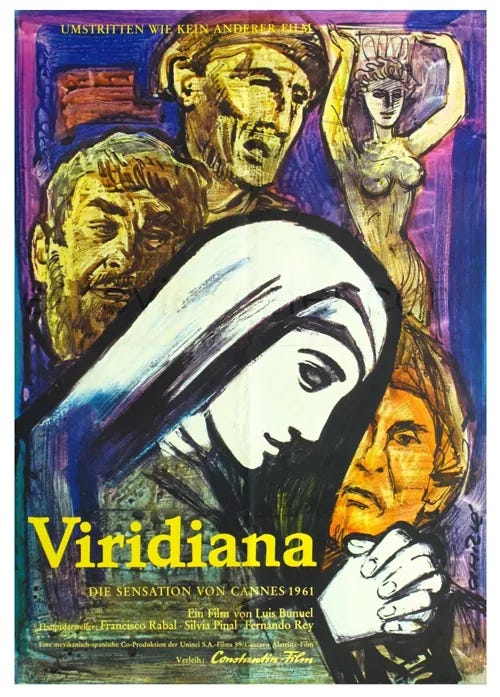

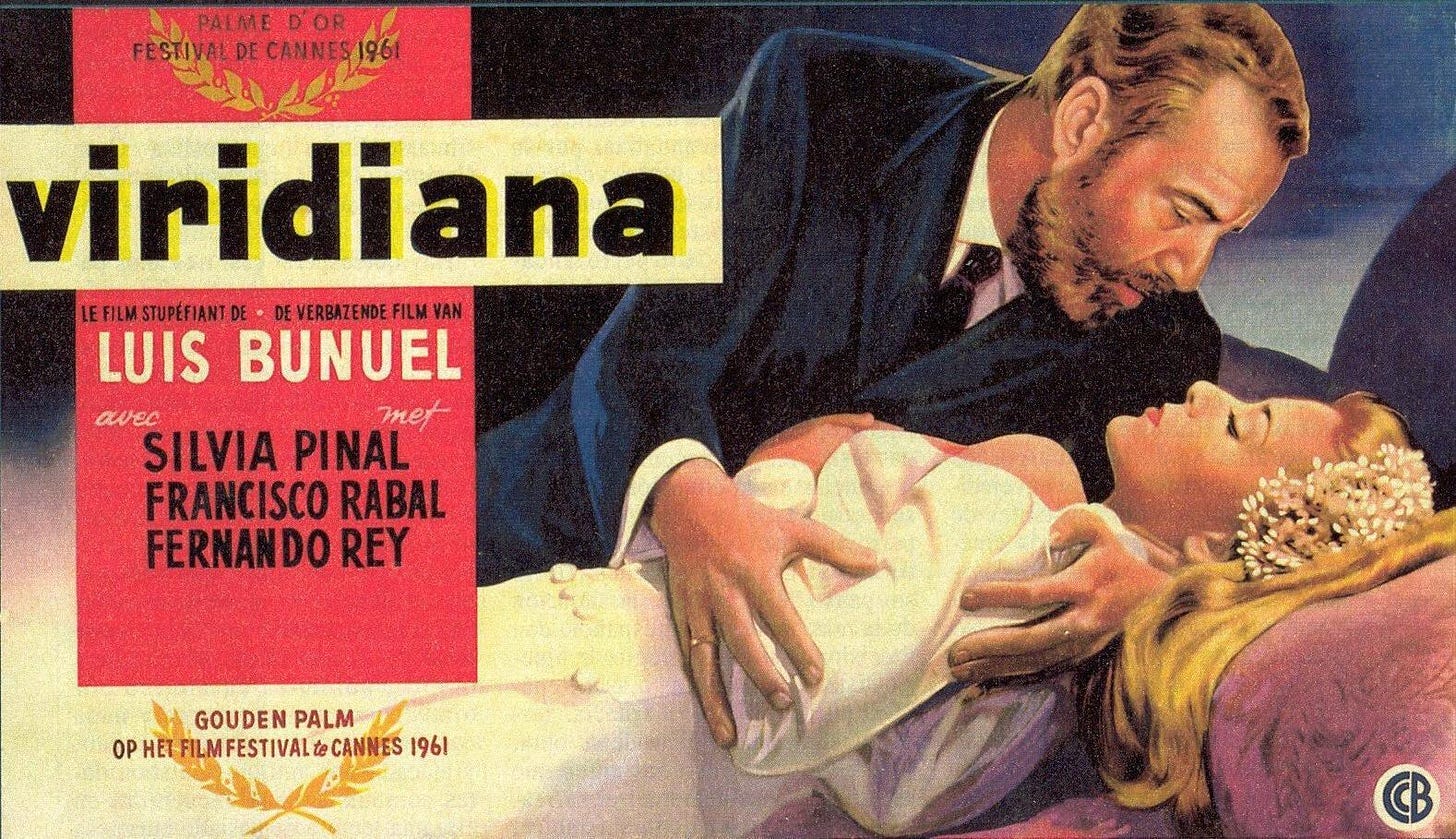

Viridiana and the Humane Cruelty of Luis Buñuel

This week has not been a great one for productivity. Because of this, and because this past week saw the 124th anniversary of the birth of Luis Buñuel, I am sending out a piece I wrote previously on the film that, in the year that both he and the 20th century turned 61, won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and launched him back into the forefront of world cinema (though Nazarin, released two years prior, feels like a warm-up in its narrative and themes and has risen to be an almost equal favorite as the years have gone on).

The full piece is excerpted below. Normal operations to resume next week.

———

Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana is at once a scathing indictment of religious decency and a celebration of human freedom. The film tells the story of a young novice, soon to take her final vows and become a full-fledged nun, who is summoned for a final visit by her only relative - an aging uncle who, though they have no personal relationship, has been supporting her financially. The aging benefactor is a sad, lonely old man who has developed an unnatural level of affection for Viridiana because she bears a striking resemblance to his wife, who died on their wedding day before they were able to consummate their vows. When his true intentions are revealed, Viridiana is disgusted and declares that she will leave the next day. So, he does what any rational man would do: he asks her to put on his dead wife's wedding dress while his servant drugs her tea so that he can take advantage of her that night while she sleeps, but when he can't quite bring himself to go through with the assault he simply lies to her the next morning and tells her that he did, so that she will believe herself defiled and be thus unable to return to her order.

That doesn't work out so well, and so he reveals the truth to her in a desperate bid to prove to her that he can be trusted and, more importantly, to express how plainly vital it is to him that she stay. But she is unmoved, and so packs her things and heads for the nearest bus back to the convent. As she is boarding, however, she gets news that her uncle has hanged himself. She thus returns to the estate, where she and the old man's estranged son, Jorge - who also develops sexual feelings for Viridiana and begins a quest to rob her of her virtue - have been named executors of the estate. Stung by her uncle's death and now hoping to apply her ministries to the outside world since she feels she can no longer go into the convent, she turns her portion of the property over to a group of vulgar derelicts who take advantage of their new home and run rampant, defiling the property that the son has been working hard to modernize.

Upon returning home to discover the havoc wreaked by her charges, Viridiana is nearly assaulted by one of them, saved only when Jorge convinces another to murder the would-be assailant. Her vagrants scattered from the property in the aftermath, the last remaining traces of her earnestness gone with them, Viridiana finds herself drawn one night to her cousin's bedroom, where it is implied that she will engage in a menage-a-trois with him and the only remaining servant in the house.

The film is, on the surface, a blistering desecration of the notion of purity itself as well as the folly of charity and good deeds. Viridiana is compensated for her piety by an ongoing series of assaults against both her virtue and, eventually, her life. When she tries to use her newfound wealth to help the poor and disenfranchised, she is rewarded with defilement of her property and her person. In one of the film's most famous episodes, Jorge chastises a wagon driver for cruelly pulling a dog behind his cart on the road. He buys the poor animal in order to spare it further grief, and as he walks off, we see another cart with a similarly yoked pup driving behind him in the other direction, unnoticed.

Why is it then that this movie fills one with so much delight? Sure, it is a joy to watch as Buñuel, that great unsullied iconoclast of the cinema, tears away at the superficiality of our senses of decency and morality, to watch as he punctures the self-inflating piety of those who superciliously order their lives around what polite society deems "the correct thing." Perhaps it is because, as viciously as Buñuel deflates the value in everything a so-called civilized society would hold to be moral and decent and good, he is doing so in an attempt to get at the true nature of humanity, free from the limitations of a hypocritical morality that denies who we are. Buñuel is a genius and a revolutionary, but his acts of cinematic terrorism are enacting a more subtle form of subversion - his is a desire to liberate the mind and the imagination from those forces which, even with the best intentions, would restrain and inhibit them. In doing so, he is liberating human existence from the shackles of banality and refusing to let us settle for anything less than the transcendent.

Viridiana is perhaps most famous as the movie that Buñuel made for political and ideological arch-nemesis Francisco Franco. In the late 1950s, more than a decade since his ascendancy had led to the director's ultimate self-imposed exile, Franco invited Luis Buñuel back to his birth country to make a film. An extreme ideological leftist who was in his personal life more moderate than some of his more anarchic compatriots, Buñuel was nonetheless a lifelong communist who had been extremely vocal against the Fascist regime - even going so far as to carry out espionage missions for the Republican Guard. Franco's thugs had recently assassinated Federico García Lorca, a friend from Buñuel's days in the Residencias of Paris and one of numerous artists, thinkers, and otherwise “deviant” undesirables eliminated in the wake of the Loyalist uprising.

It thus came as no small shock to his most ardent supporters and comrades when Buñuel, the ultimate firebrand, accepted the offer.

It is easy enough to see Viridiana, the spawn of this unholiest of alliances, as nothing less than a knife plunged deep into the heart of Franco's Spain. Indeed, the picture is often read this way, and its release (once Buñuel had returned safely to his adopted home of Mexico City) certainly vindicated Buñuel in the eyes of those Anti-Francoists who had been calling for his head for his acquiescence. This accounts for a great deal of the pleasure we take in watching as Viridiana's purity is kicked around and sullied much like that of Buñuel's home country at the hands of Franco's thugs - it is a direct assault on every value that a fraudulent idealist like Franco would hold dear. Yet Buñuel is clever enough that, even when his films work as very sharply pointed attacks on societal institutions and human hypocrisies, they are incredibly more nuanced than they are often given credit for even by some of his greatest admirers.

Ultimately, the failure of Viridiana's ideals is due to the simple fact that she holds the world to an unrealistic standard. Her mistake is not that she indulges in charity to scummy vagrants, but that she sees them as pure, unfortunate souls rather than the multifaceted and problematic human beings that they are. Her sin is not an excess of virtue but a stubborn naiveté that does not take into account the way the world really is. Jorge, by contrast, is not brought low for indulging in his charities, because he is also capable of navigating a morally fluid world. He has no illusions about the nature of the universe nor his place in it - note the way he immediately plans to bring electricity to the manor rather than allow it to continue existing within an inefficient past.

The episode with the dog, for instance, is more Rorschach than condemnation of good deeds. Yes, he saves one poor animal only to turn and thus cast a blind eye on another in the exact same position, and yes, this could easily be read as a comment on the ultimate futility and inherent hypocrisy of charitable acts. Yet should he not have saved one dog just because there are countless others who are likely to suffer? Rather than Buñuel commenting on the futility of charity and good deeds, it is his honest demonstration that we live in a world where they make, at best, merely a miniscule dent without changing either the bigger picture or the larger scale injustice of an indifferent universe, because that’s ultimately something that to him cannot be changed by individual actions.

Even the ultimate destruction of Viridiana's ideals is not so much a defeat as a victory in Buñuel's eyes. Free of her empty piety, she is able to truly live. In this way, Viridiana is even more of a subversive work than it gets credit for. As not only an assault on the kind of values that Franco went to unimaginably evil acts to conserve, it is a film that dares to suggest the inherent humanity of every character. A humanity that always triumphs over the false imposition of religious doctrines or self-imposed asceticism. Granted, for Buñuel humanity is messy, inconsistent, unreliable and, most importantly, unable to live up to the ideals that extremism is always in such a rush to impose. Yet the most powerful tool that the artist and the revolutionary have in their arsenal is the truth, and Buñuel not only refuses to flinch and turn away from the potential ugliness of its application, but rather revels in that ugliness as proof of the beautiful, miraculous randomness of existence.

- cs