Until August

A delayed goodbye and a grappling with the meaninglessness of qualitative responses to art

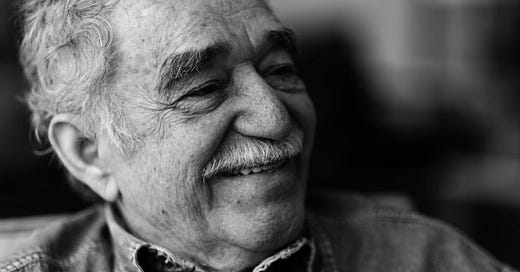

In mid-March I stumbled across a link to a review of a new novel by Gabriel García Márquez. While the idea of an author continuing to write and publish fiction over a decade after his death seemed like the perfect continuation for the career of the great magical realist, the truth was something far more commonplace: his children, along with his former editor, had dusted off an unfinished manuscript. While this dimmed the rush of excitement I had felt somewhat, I was nonetheless levitating at the prospect of reading a new work from so cherished an author.

His larger literary and cultural bona fides aside, García Márquez is a massive figure in my own development. A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings was, along with Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, a definitional read for me. They were my introduction to works that played with the nature of reality and perception. This was shortly before I would see Mulholland Drive and thus be properly introduced to the films of David Lynch, which would then send me on my way to discovering Buñuel and the other cinematic surrealists. And this was years before Esslin’s The Theater of the Absurd would become something of a bible for me not only in its cataloguing of writers who resonated with my own stylistic interests but also in the way that it gave concrete expression to what it was that appealed to me about those works and, by extension, the abstract and the inexplicable in general.

It was actually after seeing Mulholland Drive in freshman year of college that I went back to García Márquez and started reading more of his work. I would often check out a copy of his Collected Stories while in college (or maybe I checked it out and kept it long past its due date?) and carried it with me as something of a guidepost. When I feel lost and in need of a way to approach something of my own, he’s one of the figures I think about. It wasn’t until a little later that I read One Hundred Years of Solitude, which very quickly became something of a north star for me. Not merely my favorite book, but perhaps my favorite piece of art period. In fact, when I think of what art should be, what all art should strive to achieve, that’s one of the first things that comes into my head. There is a specific passage in that book that I measure everything I’ve ever done up against, in the hopes that I might one day match the effect that it had on me.

I haven’t come particularly close, obviously, though I suppose that’s what keeps us going.

Anyway, all of this is preamble to addressing the new book itself while also considering the circumstances in which it has been released. It’s a curious thing because, while what we have is not necessarily unfinished or sloppy – it was re-worked multiple times while García Márquez was still alive (a portion of it even appeared in The New Yorker) – it is nonetheless unfinished in that it feels like a brief sketch of something meant to be larger. Further reading revealed that it was meant as the first in a series of short novellas centering around the main character, Ana Magdalena Bach. While the portion we’ve gotten was in essence finished, the larger project was abandoned due to the loss of memory that García Márquez was beginning to experience as a result of dementia.

The novel that we’ve been left with centers on Ana Magdalena’s yearly trips to the Caribbean island on which her mother has been buried. In the first chapter Ana, happily married, has an encounter with a man at the hotel bar that leads to a one-night stand. When she awakes the next morning, she finds that he has left her a twenty-dollar bill. Horribly offended, this sets her on a course where every year she will come back to the island and take another lover. We get brief snippets of her home life occasionally between these episodes, in which we get a sense not only of how her illicit encounters are effecting her home life but also how they are uncovering the resentment she feels towards her husband for his own affairs.

Thankfully, the book doesn’t necessarily go where we fear it could go. Ana Magdalena is not punished for her transgressions, nor do her dalliances tear her marriage apart nor forge any kind of new understanding with her husband. The book is far more interested in how these actions serve to illustrate the unknowable chasm that ultimately exists between our ideas of ourselves and who we actually are and, by extrapolation, between us and the people we love most. This even extends to Ana Magdalena’s mother, around whom the book’s ultimate revelation is centered. In the midst of all of this we have García Márquez’s usual facility with language (translated here by Anne McLean) and his keen attention to detail. Few writers have the ability as he does to make the most quotidian of details feel transcendent. There are little to no magical realist touches here, save for a bag of human remains that calls to mind little Rebecca carrying her parents’ bones in a sack with her everywhere she goes in Solitude.

After reading the book in 1-2 sittings I started looking over reviews and found them largely uninteresting. Most painted it as a minor work and something of a disappointment; some even suggested it never should have been published. They’re missing the point, of course, but this is also getting at something that I’ve been thinking about for quite a while now which is the pointlessness of discussing art, literature, movies, etc. in purely qualitative terms. Some of this is age, and some of this is how my relationship with the media I engage with has changed over the years, but I also find that as we move more and more into the era of…shudder…content, where things are made and released with the goal of being consumed and disposed of as quickly as possible, the more we depend on quick and extreme reactions. “That was the best” or “that was the worst” seem to be the only reviews acceptable. Forget about nuance and forget absolutely about any consideration that isn’t about whether something can be recommended or condemned to friends or “wittily” summed up online.

I’m also at a point in my life where I’m far less interested in a successfully crafted piece, whatever that even means, than I am in something that reveals a worldview or makes me feel as if I am in conversation with a specific and active intelligence. While I happened to enjoy Until August, I also appreciated and was interested in it as a work that was incomplete. I took it not as a final statement from a great artist, but as something that a writer I admired struggled with and ultimately gave up on – which is ultimately much more interesting to me, but also much more rewarding and, in its own way, of a piece with his larger body of work because it deals in its own meta-textual way with one of the painful truths within the beautiful, strange, and vexing experience that is being a human being in this world.

-cs