I have, for some completely and utterly indiscernible reason, been drawn as of late to read and revisit writers and filmmakers who worked directly under, lived in exile out from under the distant shadow of, or simply dealt thematically with totalitarian regimes.

(My knowledge in this regard is admittedly very Western/Eurocentric and so I would love recommendations of anyone who fits this schema beyond that; if you have any, send me a line or post a comment.)

It started earlier this year when I re-read Ionesco’s Rhinoceros for the first time in over a decade and was struck by the parallels to Trumpism - even more so this go-around than previous cycles, in large part due to the increased normalization and sane-washing of his ever-more hateful and destructive authoritarian impulses which, combined with a media that seemed all to eager to welcome him back into power, made me feel at times as if I was one of the only people in the world not going insane.

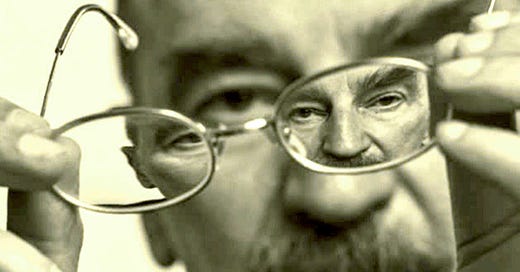

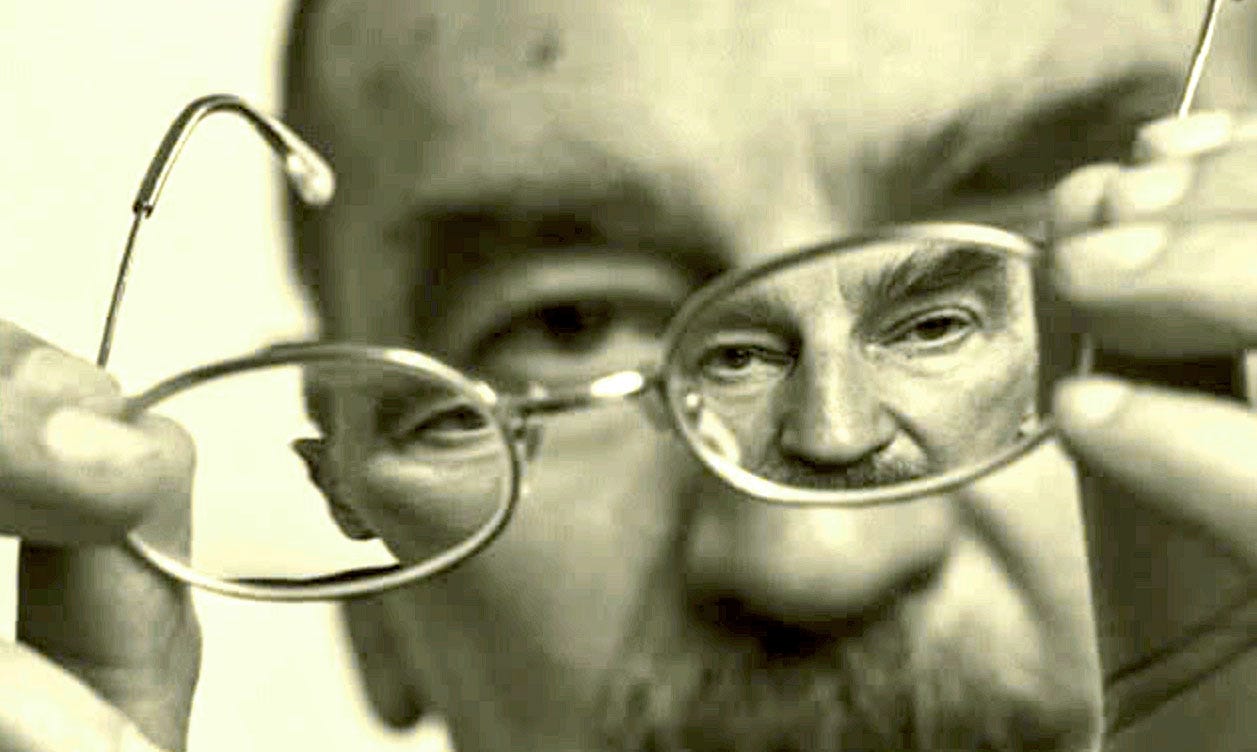

Most recently I’ve been reading Sławomir Mrożek, a short story writer and dramatist who started writing in his native Poland before defecting in the 1960s. Mrożek is in the tradition of the Theatre of the Absurd; though his work deals much more directly with then-current political realities than other Absurdists, he depicts the inherently ludicrous psychology of authoritarian states and those who live within and succumb to them in a way that gives him claim to that lineage. I first read Out at Sea, in which three well-dressed men trapped on a life boat engage in a perversely logical debate over which one of them the other two will eat in order to survive, last year. The play ends with one of the men, Thin, having fully accepted, rationalized, and narrativized his fate as the one to be eaten; the other two men then find some provisions hidden elsewhere on the raft, but decide not to reveal this as Thin has so definitively embraced his fate.

It feels somehow apt these days.

His short stories certainly hit home fairly often as well. In The Elephant, a corrupted government agency cuts so many corners in procuring a new elephant for the local zoo that they fashion a realistic-looking inflatable animal that ends up getting caught in the wind and floating away when a group of school children come to visit. A Drummer’s Adventure ends with the titular military musician, idiotically full of patriotic fervor and so zealously beating his marches night and day, arrested for treason by the General whose sleep he has been disrupting.

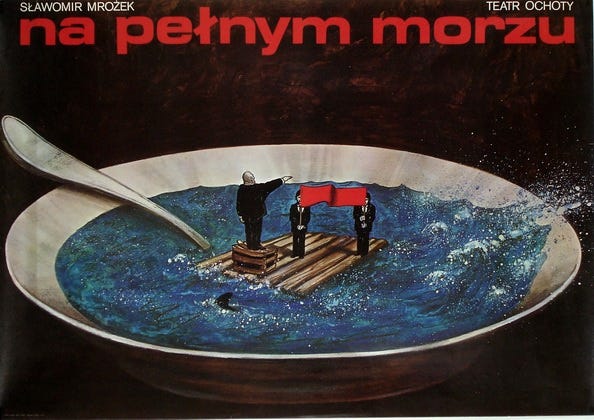

Mrożek’s first major play, The Police, begins with the last political prisoner in an unnamed country (embellished just enough to avoid any comparisons to Mrożek’s own; absurdity and clever-enough satire were powerful tools for avoiding censorious backlash from the very government he was lampooning) making the case that he has been fully reformed and signing an oath of loyalty. Upon his release, the police suddenly realize that they have no one else to arrest and thus no longer serve a purpose. In a world where all rebellion has been stamped out, what is an oppressive regime to do? The answer, of course, is to turn on each other - the Chief orders his most loyal officer to defame the king so that he can arrest him on the spot. By the end of the play, the arrested officer has been radicalized by his imprisonment, the last prisoner released returns as the second-in-command to the very General whose attempted assassination placed him behind bars to begin with, and they all engage in a triangulated standoff over who should arrest who.

Oppression is thus a state of mind. Like anyone who ever had to live under authoritarian rule, Mrożek feels no need to write directly about the leaders of those governments because they are only the starting point of the threat - the true fear lies in the knowledge that fascism is an infectious disease that propagates itself by changing the way that the citizens who live under it think. And when they no longer have an other to go after, they will start going after each other and themselves. In Charlie, an eye doctor is terrified by a young man and his grandfather, who come into his office with a shotgun looking for someone with the titular appellation in order to gun then down. By the end of the play the occultist has given up his own glasses and offered up one innocent victim while setting up another, all to save his own skin. And like the three stranded travelers of Out at Sea, the identical men who wind up for reasons they cannot remember tapped with the mysterious room in Striptease are quick to adjust to their drastically altered surroundings, readily obeying the giant, menacing hands that periodically come in through the side doors.

Mrozek is perhaps so tapped into the totalitarian mindset because he seems to have been, at least publicly, a part of it until he left Poland in the 1960s, though as he had started writing in the late fifties his seditious leanings may have been somewhat apparent even before then and only safe to fully express after his defection. In any case, he seems to have avoided government intervention with his earlier works because of their heightened manor, their use of absurd situations, and their overall stylized and comedic sensibilities. Much like Luis García Berlanga was able to satirize Franco’s Spain right under his nose, Mrożek demonstrated the power of comedy when wielded for a purpose and with intention. Some of this is simply due to the pure fact that if people are laughing, they’re disarmed; but they also don’t take you seriously, and so you can get away with more. The irony here is that while they are discrediting you in the moment, the comedy tends to linger longer because it strikes at such a primal level, which means that it can also sting all the more sharply when properly deployed.

“In our time, only farce is possible.”

Jaroslaw Anders, from Sławomir Mrożek and the Shades of Absurdity - A Lecture

While dreary and realistic depictions of unjust societies can sometimes fall flat or not linger in the consciousness as long, more stylized treatments tend to gain power through their irrationality. They fail to make sense in the same way that the world fails to make sense. Of course now, in a time when day-to-day reality seems to operate at levels beyond even our most absurd imaginings, farce becomes perhaps the only logical response - whether to further extrapolate the nonsensical nature of what we’re facing, or perhaps to circle back around and somehow wrangle it back to earth in order to properly face it.

One of the things that those of us drawn to the absurd or the comedic have to contend with are the complaints that the works are too frivolous, too obtuse, or ultimately meaningless. Of course, sometimes the meaninglessness is the point, but the larger consolation for disregard is that time is sometimes kinder to those who pushed against systems rather than trying to work within them. Part of why I have always been drawn to the Theatre of the Absurd, as I’ve written before, is that they were working from an understanding, however innate, that the old ways of the world had led to nothing but death and destruction. Eons of human civilization culminating in two world wars and the atomic bomb, a weapon that was capable of destroying the entirety of life on the planet. Established literary and dramatic forms were emblematic of that, and as such they needed to be broken apart and left behind in order for us to move forward. It was also a way to break free of cliched thought, of an automatic and non-critical existence that allowed despotic systems of power to exert influence and gain hold within all walks of life. The stagnation and calcification of language, and of our narratives, had rendered us susceptible in our complacency.

Perhaps it’s time to start thinking about that again.

-cs