Class prep, which theoretically happens in the back halls of the mind for most of the semester previous, realistically happens in a mad dash during those one to two weeks after New Years when most everyone else has gone back to the office. I was 1) lucky and 2) good this Spring in that most of my classes were ones I had taught before and so the bulk of this week’s work was finalizing syllabi and building course pages, changing dates on a schedule, and making any updates I saw necessary after previous semesters. Nonetheless, it gave me time to consider my approach to class preparation - particularly as it relates to this specific time of year.

It's appropriate that a new semester start with the beginning of a new year because I find that I tend to approach each in the same way. A new semester, like a new year, is a perfect thing because it hasn’t happened yet. It hasn’t had a chance to challenge you or wear you down. It is a projection made up entirely of your intentions and your idea of who and what you are and can be as a teacher, as a human. “I’m going to get students excited about the mechanics of sound editing” can be as aspirational as “I’m going to write a page of script every morning” or “I’m going to read for half an hour before bed every night.” And much like each year’s resolutions tend to most often be new or developed approaches to goals or habits that have persisted for an entire life (one year getting healthy means exercising more, another year it means no longer eating refined sugars), so too does each semester’s specifics present a new way of approaching learning objectives that have been set in place long ago, oftentimes before you were even teaching the course.

This is most evident to me this semester in two of my classes – Audio and Post-Production. Audio I’ve taught before, while Post-Production is new to me. In each case I’m being guided by pre-existing approaches and materials – my own in the case of Audio and previous instructors in the case of Post – that I’m now charged with either refining and correcting or making my own. And I’m equally excited for each – to improve on what I think were deficiencies in my approach to Audio last go-around, and to get back to a subject I taught regularly long ago in a new mode with Post. I have high expectations for each – expectations about my performance, about how engaged the students will be, about the effectiveness of the lessons and assignments. I’m trying to approach each the same way I approach every course, by designing and presenting it in a way that would excite me in the hope that this excitement will be contagious. What I know from my years of doing this is that like any contagion, some will get it and some will not. That’s the nature of the beast. It can be hard to simultaneously embrace and let this go while also continuing on and adjusting in a way that makes a course as successful as possible for as many as possible without compromising its basic integrity.

Because like a new year, it can be just as crushing when the intentions and promise of a new semester crash up against the rocky shores of reality, be it through attrition or through the stubborn refusal of the rest of the world to bend to your desires.

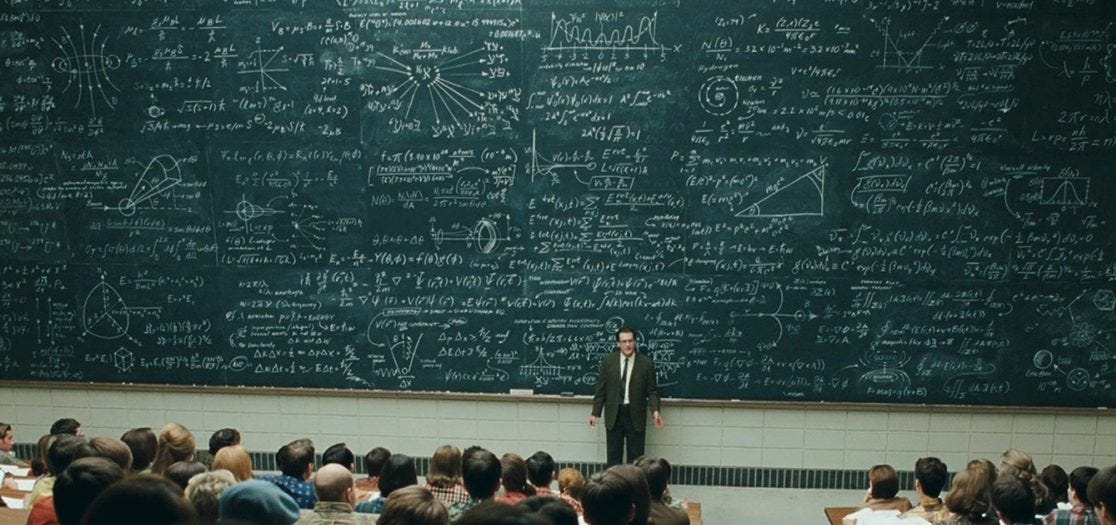

When I first started teaching almost ten years ago, I operated from the position that there was a platonic ideal of what a professor should be, and that if I didn’t achieve this then I was a failure. This proved somewhat self-fulfilling as this approach provided results as uninspired in this field as it has in any other in which I have attempted it. It took some trial-and-error, and a lot of development, to figure out why this was the case and to reach an approach that felt more successful both for the students and for myself. I never took any courses in pedagogy, and so most of this has been discovered through on-the-job training and through discussions with colleagues and friends.

A lot of what stymied me originally was the idea that I had to be an infallible expert on all things that I was teaching. And while it is true that I am in the position I am in because my years of education and experience have granted me somewhat of a comprehensive knowledge of the subjects I teach, it took some time for me to embrace the fact that any gaps in that knowledge were not deficiencies but areas in which to continue learning – and that any time I could do so along with students was enriching not only for me but for them as well. I usually know more (though sometimes I may not), but I don’t have to know everything because what higher education is, or what it should be, is on the one hand an act of discovery wherein I in my experience and expertise guide, lead, and mentor them, but also on the other an act of teaching them how to engage in that act of discovery for themselves – and there’s no more effective way to do that then to engage in the process right along with them and thus provide a live, in-the-moment template.

This is a large part, I think, of why project-based education has become all the rage in pedagogical circles. I’m lucky to be in a discipline, and in a department, where this is inherent to pretty much every class I teach. It’s practical, it’s engaging, and it provides a host of unpredictable real-world problems the solving of which opens doors of discovery and engagement that can’t always be anticipated no matter how carefully one plans.

In re-reading Walter Murch’s In the Blink of an Eye in preparation for my Post-Production class, the following quote leapt out at me. Murch is talking about the virtues of simplicity over needless complication when it comes to a sound mix (it’s not about how much is there but about the choices that put what’s there in place, he argues), but his ultimate point applies, I think, not just to sound design but to filmmaking, or even any and all art, as a whole:

“The underlying principle – always try to do the most with the least […] because you want to do only what is necessary to engage the imagination of the audience – suggestion is always more effective than exposition. Past a certain point, the more effort you put into wealth of detail, the more you encourage the audience to become spectators rather than participants.”

Replace “audience” with “students” and this can apply perfectly to teaching as well. When I started out, I wrote out and scripted every lecture down to the syllable, and the results were always the same – I would freeze or get easily distracted because I was trying so hard to hit all those pre-ordained beats, or the material became completely unengaging because it was set too deep in stone. It was like we were examining a body lying dead on a slab, where the classroom discussion should be a living breathing thing. What I’ve realized is that my classes are so much more successful when I make general bullet points of all the important notes that need to be hit and figure out how to get there as I go – because then I can also react better to in-the-moment developments, tangents, and questions.

This is where the aforementioned expertise really comes in handy, by the way – when your own insecurity makes you worry that you’re not doing enough, you step back and remember/realize that you’ve spent an entire life preparing for this, stockpiling knowledge and experience that fills in those gaps. A lot of the work has been done already and the effort now goes into simply giving its resultant lessons a framework and an outlet. The insecurity looks at the phrase “most with the least” and “only what is necessary” and thinks of corner cutting; only time and the accumulated wisdom of experience puts those phrases within the proper context. Much like a master artist hones their style to its maximum simplicity as they age, so it is with teaching. And as with life, we’re more successful when we go in with the strongest possible plan but also leave that plan open enough to the whims of chance and fate, prepared to roll with what the universe throws at us along the way.

Not that I’m all the way there yet, but again – it’s a process.

-cs