Hollywood Apocrypha: The Bold Reclusion of Keva Rosenberg

Another entry in the absurdist alternate history of America’s dream factory, focusing on people who never made it to the center of the spotlight, primarily because they are completely made up.

I had already ventured far off the grid in order to get the location of the compound. Cell service was spotty and so the GPS only got me so far, and while the directions that had been provided bore no trace of the influence of technology, so disinterested did they seem to be in convenience or legibility, I was able to piece together a sequence of steps from their loose collection of suggestion and inference. It nonetheless took a while once I got to the designated site to find what I was looking for – a rusted iron gate of the type one usually finds enclosing horses or disused farm equipment, reinforced with what looked like an extra-secure bolted lock and adorned with a large yellow sign that warned anyone approaching of the 50,000 volts that were allegedly coursing through its bones. A small intercom sat some 25 yards in front of the fence, and it was here where I stopped my car and pressed the small red button.

At first there was only a loud crackle in response, which soon faded into the low white noise of an open radio line waiting to be filled in with speech. I continued waiting for some kind of prompt, though one never came. What started as curiosity started to transmute into a low uneasiness as I began to wonder if this was my first test – that perhaps the person I had come to interview, who presumably sat at the other end of this radio connection, was so disinterested in being disturbed that they didn’t even want to give me the chance to explain myself, and were merely waiting for my own self-justification.

“I’m here about the interview….” I finally offered.

Silence.

“I left you the series of phone messages, and you sent me a letter in response?” It had come from an unmarked address and had very clearly, now that I was here, been routed through a far-off post mark.

Still nothing.

“If this is a bad time, I can always…”

There was the loud grinding of metal on metal, and as the gate started to open I noticed that it did so with the help of a system of gears and belts which led underground and, one had to assume, all the way to a nob or, most likely, a turning wheel operated at this very moment by the same person sitting at the other end of this open intercom communication.

“Keep going straight,” a modulated voice croaked over the speaker. “You’ll know it when you see it.”

I said “thank you,” but the connection had been cut before I could get the first word out, so I simply drove ahead lest he change his mind and close the gate again. I had wondered if the fence was in fact electrified or if that was merely a feign against intruders, but as I drove across the threshold I noticed the charred remains of an armadillo, still fused to the bottom rung of the gate, its body contorted in its final brief yet eternal moment of horror and pain.

The grinding began again, and the gate closed decisively behind me.

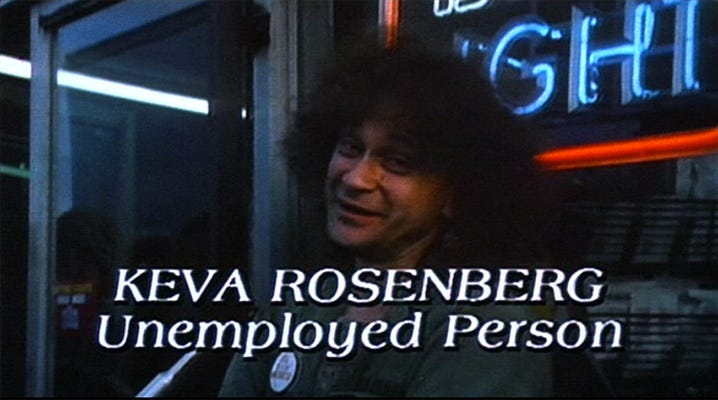

I first stumbled upon the name Keva Rosenberg by accident when I was perusing an early draft of Walter Murch’s In the Blink of an Eye for a grad school paper. In the earlier version of his chapter on Apocalypse Now, Murch originally mentioned a consultant brought in to help with the sound mix. This individual, he explains, was cantankerous and difficult – refusing to be in the same room with the other technicians and assistants, he performed all of his work remotely because, as he put it, spurious human contact would only taint his process. In spite of this, the work he turned in was brilliant, and as Murch described it seemed to have provided the much-needed spark of inspiration that led director Francis Ford Coppola in the direction of a more surrealistic and expressionist approach to his war epic.

If one finds themselves wondering why Murch and the rest of the post-production crew would have put up with such hurdles from someone who was not an official member of the team, it’s because Keva Rosenberg had by that point proven himself an immense figure in the recording industry – but only for those in the know, as his presence among some of the major revolutions in sound technology had been scrubbed from the record, and largely at his own insistence. In digging beyond the official records and contacting any and all inside sources I could find, I was able to piece his legend together somewhat, but even then it was a half-formed tale with lots of gaps. The only things that everyone I talked to agreed on were that they had no idea who he was or where he came from, that he did all of his work remotely and in response to pre-existing materials in need of elaboration - he was a fixer more than a guide or initiator - and that his work always came fully complete, ready to be integrated with the final piece, and with the reiteration of a term from his contract that he owned rights to all the raw recordings - likely so that he could destroy them and prevent their reuse. Beyond this I only ever considered a claim verified if it was backed up by at least one other source, and so while I can say with some confidence that he was involved in some capacity with the recording and mixing of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Dark Side of the Moon as an associate of Alan Parsons, and that he was a major behind-the-scenes proponent of the first use of stereo recording for a film during the finishing of the Streisand version of A Star if Born. And while I’m split on whether or not he did indeed have a part in creating the NAGRA sound recorder along with credited inventor Stefan Kudelski - while I heard this from multiple interview subjects, the specific accounts varied too widely to be properly collated - I rejected the individual claims of collaboration with Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart - two artists that he likely would have despised since, despite his innovative approach to recording, he was repulsed by anything even vaguely counter-cultural or even abutting against the avant-garde.

It was also this distaste that became the sticking point between Rosenberg and Coppola, as Rosenberg originally thought he was lending his services to a film that, while anti-war, would nonetheless conform to a more traditional narrative approach, and the more the latter pushed the film in a hallucinatory direction (a decision based again, and ironically, on Rosenberg’s own contributions) the more the former disowned his involvement to a more active degree than his usual passive self-erasure. In response, the hot-blooded Coppola made more and more strenuous insistences that the mercurial sound tech had nothing to do with his film – to the extent that it was likely at his insistence that Murch erased any and all reference to him from his book. It was a fracas that threatened to give the already-reclusive Rosenberg a degree of attention that he had never wanted, and so he not only backed down from his quiet role in the scuffle but retreated even further from the public. And rather successfully, as the only public reference to him beyond Murch’s early draft is the strange fact that a blink-and-you-miss-it character in Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop bears him name on-camera.

It was only through my strenuous - and likely unprecedented - efforts that I was able to locate a patch of land that he had purchased long ago via family money and upon which he had, using his not-inconsiderable royalties, built up the compound into which I was now entering.

I say “compound” even though the allotment of land was rather small and laregely free of any signs of human civilization or encampment. As I continued on as directed, I passed by a series of sculptures that had been assembled in a way so as to minimize any evidence of their conscious construction – as if whoever had made them had wanted them to appear as natural, spontaneously occurring entities. And they had mostly succeeded – they each looked like only-somewhat carefully arranged piles of trash upon first notice, and yet each produced its own unique soundscape as I drove past. A constellation of glass bottles whistled at me as I drove past; a flowering of aluminum cans chiming in rhythm with the wind.

I didn’t see the buses until I had passed over the crest of a hill roughly halfway across the property. I realized once I did that the hill was circular, a berm wrapping around and hiding the vehicles within what almost looks like a large crater when you’re on the other side and yet looks like flat land from the outside. I begin to wonder if this is also man made.

I say “buses” and you may think of busted-out, dilapidated school buses, or perhaps a team of old boxy VWs, but this is a much fancier affair. They are in fact a 3-bus tour fleet that he purchased from Ratt at a discount shortly after they disbanded – the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria, as the signage indicates. The Santa Maria lies perpendicular to the end of the rutted roadway with the other two branching back in a u-shape, and so I park in front of her an approach the door. Like the front gate to the property it is automated but in an analogue, Rube Goldbergian fashion. Unlike the entry to the compound, it is unlocked and provides easy and immediate access to the inside.

I expect it to be hotter than blazes when I enter, but it’s rather temperate – likely to avoid any damage from heat or humidity to the recording equipment and reels of tape stored within. Any HVAC system in use is however completely silent, which I imagine is the result of careful soundproofing. I take a look around the unit in which I’m now standing and I see that it is lined almost in its entirety with racks containing cannisters of magnetic reel-to-reel tape. On closer inspection I see that they are all labeled in a fine yet forceful hand and bear names such as “The Birds, Reels 4-6”, “Jurassic Park Reels 2-5,” and “The Matrix, Reel 1-3” to name just a few. I feel a flurry of butterflies in my stomach as I wonder whether I’m discovering a trove of heretofore unknown collaboration on some of the most sonically innovative movies of all time, or if this is rather the archive of a hobbyist – someone who no longer does the work professionally and yet can’t help themselves from re-tracking effects from some of their favorite films.

I’m not sure which possibility I consider more exciting, and I’m debating between the two when a third possibility occurs to me. As someone who has kept such a tight control on his image and on even the knowledge of which projects he has worked on, it’s surely not an indiscriminate lapse that I am here on this bus, looking at these cannisters and resisting the urge to run out of here with all of them. I’m in this bus because he wants me on this bus, and if I’m looking at them it’s because he wants me to. It could all be a giant head-fuck by an embittered old hermit who has decided to play an elaborate prank on the one person in the last 40-odd years who has had the gall to track him down and bother him.

I strongly consider picking up and opening one of the canisters to look inside when two things stop me. One is the notion that this would surely be what he wants me to do and that to indulge would thus be failing some kind of test of my character. The other is a loud and persistent single-tone buzz coming from somewhere inside the bus. I look around until I find the source – a small red button much like the one on the front gate intercom, placed under a large wall-mounted speaker, that lights up with the sound. I approach it, press it, and the noise stops.

And suddenly that familiar, heavily-moderated voice comes over the speaker.

“What do you want?”

“I’m here for the interview.”

“What interview?”

“With you? You said in your letter that—”

“With me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Who am I?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Why would you want to interview me?”

This feels like another test, a trick question that I have no idea how to answer, and so I don’t.

“I think someone gave you some faulty information,” the voice says.

“Well, could we speak in person so that we could clear up whether that’s the case?”

“I think someone gave you some faulty information,” the voice repeats.

“I understand your need for privacy, and I don’t want to expose you to any unwanted attention, but I really think there are people who would love to hear your story.”

“I think someone gave you some faulty information…”

It’s then that I notice the two-way mirror on the other side of the bus. I approach it slowly, not wanting to be seen as an encroaching threat or as someone who can’t take a hint. But it turns out I needn’t have bothered. Peering into the mirror at the right angle allows me to see a ghostly yet conclusive image on the other side – a reel-to-reel player whose mechanism has somehow gotten stuck and loops the last several inches of tape over and over.

“I think someone gave you some faulty information…”

Before leaving, I grab a canister on the wall marked “Superman, Reels 6-8” and, before any security system can stop me, I run out with it.

I wouldn’t have been able to live with myself if I hadn’t checked the other buses, and so I knock on the door of each but get no response. I try to open their doors, but they are locked. The windows of each, completely blacked out to protect whatever is inside from the scorching sun, offer no clue as to their contents.

And yet I’m not dejected as I walk to my car and start the long drive back to the entry gate. Worst case scenario, I have been the victim of an elaborate con by one of filmdom’s most reclusive figures, and as such I have at the very least confirmed an existence that months ago I wouldn’t have been entirely sure about. And I even have proof sitting on the car seat next to me.

It’s not until I’m beyond the property line that I begin to wonder again if the ruse was in fact perpetrated in order to prove my worthiness, and it is at this point that I hear a faint pop and start to see smoke rising slowly from the seam running around the canister’s circumference. I pull over to the side of the road, rip it open, and am greeted with a flood of chemical smoke. I start gagging immediately and open my window to ventilate the car. Once the smoke and my cough have cleared, I look inside and see a tight spiraling circle of ash.

So there was something inside those reels after all. And if this was indeed a test, then I have failed.

Undeterred, I decide to drive back to the compound and explain myself. I push the button on the intercom and a familiar voice warbles from the speaker.

“I think someone gave you some faulty information…”

I press the button again. And again. And again.

-cs